The workforce is health care’s most precious resource. Hospitals and health systems are committed to supporting mental well-being and improving access to behavioral health screenings, referrals and treatment when the workforce needs it. This AHA guide, Suicide Prevention: Evidence-Informed Interventions for the Health Care Workforce, identifies three drivers of suicide: stigma, limited access to behavioral health resources and treatment, and job-related stressors. This guide offers a curated list of 12 evidence-informed interventions that hospitals and health systems can implement to reduce the risk of suicide among health care workers.

Hospitals and health systems should choose the interventions and metrics that work for their organization based on their own needs and available resources to customize a pathway to suicide prevention for their employees.

For those experiencing a suicidal crisis, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 or text the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741.

Executive Summary

Background

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), health care workers are at an increased risk for suicide for reasons such as difficult working conditions, long work hours, rotating and irregular shifts, emotionally difficult situations with patients and family members, risk of exposure to diseases, and other hazards, including workplace violence, routine exposure to human suffering and death, and access to lethal means (CDC, 2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the risk factors for suicide in the health care workforce. A study by Mental Health America from June – September 2020 showed that of the 1,119 health care workers surveyed, 93% reported experiencing stress, 86% reported experiencing anxiety, 77% reported frustration, 76% reported exhaustion and burnout, and 75% reported feeling overwhelmed. Thirty-nine percent of health care workers said that they did not feel like they had adequate emotional support.

In September 2021, the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), part of the CDC, granted the American Hospital Association’s (AHA’s) Health Education & Research Trust (HRET) a grant to:

- Identify and curate existing evidenced-based and developing approaches for addressing and reducing suicide risk and attempts in hospital personnel;

- Develop curated content of interventions, by hospital type where possible, to optimize maximum spread and adoption of suicide risk assessment and/or prevention strategies; and

- Identify metrics to assess and monitor prevention initiatives.

Highlights of Findings

To address the above objectives, a literature review, and a survey, interviews, and focus groups of hospital and system leaders were conducted. These combined methods led to the identification of three resonant drivers of suicide in the health care workforce: behavioral health stigma, poor access to behavioral health treatment, and job-related stressors. The impact of the three drivers was further explored in the one-on-one interviews and focus groups, which delved into modes and accessibility of services as well as the effectiveness of campaigns to reduce stigma and the importance of data collection, stratification and use.

While the literature review did not reveal any one specific intervention with strong evidence of preventing suicide among health care professionals, several interventions identified in the literature, survey data, and focus group and interview data demonstrated some indication of effectiveness, and a broad uptake among hospitals and health care systems. Twelve suggested interventions, as well as related metrics, are provided in the High Priority Interventions and Metrics chart.

Three Drivers Of Suicide In The Health Care Workforce

-

DRIVER

-

DRIVER

-

DRIVER

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic and its effects have created unprecedented stress, anxiety, and uncertainty for health care workers. Health care workers at hospitals and health systems across the country have felt the effects of caring for their patients, families, and communities over the last two and a half years, and research shows that health care workers have reported higher levels of psychological distress, stress, anxiety, depression, burnout, sleep impairments, and work impairments as compared to before the pandemic (Biber et. al, 2022, Gupta et. all, 2021). These factors are associated with psychological distress, which may lead to symptoms of anxiety, depression, or provoke suicidal ideation, and potentially suicide. Gupta et. all, 2021).

Hospital and health system leaders play a critical role in preventing suicide among their teams by ensuring that the workforce has the tools and resources needed to maintain their mental health and well-being. Findings from the literature review suggest that some existing interventions can reduce anxiety and stress, identify those in extreme distress, and connect those in distress to needed services. While the research community continues to devote more attention to this issue, hospitals and health systems can introduce or enhance resources and support to improve the mental well-being of the workforce. This guide is intended to provide hospital and health system leaders with ideas, tools, interventions, and metrics that they can implement within their organizations to improve behavioral health and well-being and reduce the risk of suicide.

Methods and Findings

Literature Review

A literature review was conducted in March 2022 to identify evidence-based best practices for preventing suicide in the health care workforce. This literature review built on a previous scan of the published and grey literature conducted by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI).

Inclusion criteria included articles that were written in the English language, human research population, peer-reviewed, primary research or systematic review, and manuscripts published between 2020-2022. Because health care workers in lower to middle income countries may have significantly different experiences from U.S. workers, primary research studies were included only if the target population was in a high-income country (as defined by the World Bank). Articles on topics related to suicide (such as burnout, depression, or moral injury) were included only if the study also measured suicidal thoughts, behaviors, or attempts. Abstracts, study protocols or program descriptions without results or evaluation, and non-systematic narrative topic reviews were excluded.

A limited number of articles not directly related to health care populations were included because they reviewed data on evidence-based suicide prevention interventions, theories of suicide, novel or emerging approaches to suicide assessing risk, or information about key subgroups with less data in the health care literature (e.g., risk by race, sexual orientation, disability, etc.).

Survey

Design

Two surveys were conducted to identify programs that hospitals and health systems are implementing to support the mental well-being of and prevent suicide among health care workers, as well as the challenges and barriers encountered in these areas. The initial survey (conducted from October to November 2021) had six responses;, and the final, revised survey (conducted from November to December 2021) had 158 responses. Excluding demographic questions, the initial survey had five questions and the final survey had seven. The survey questions were revised to address a low response rate on the first survey, and because the two surveys asked different questions, they were analyzed separately. Given the higher number of respondents and revised questions in the second survey, many of the key findings presented in this guide come from this revised version.

Survey Findings

The surveys found that hospitals and systems are implementing diverse strategies to improve their health care workers’ access to behavioral health services. Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs) were the main strategy, and; other strategies included critical incident counseling and debriefing, stress management and resiliency training, and workplace behavioral health awareness training. Psychological safety training and behavioral health education to create or increase a broader sense of psychological safety were also reported. Organization-created programs, such as peer support and wellness groups, were reported more often than nationally- recognized programs like the UCSD HEAR Program, but respondents overwhelmingly indicated that they would be interested in learning more about national, evidence-based approaches.

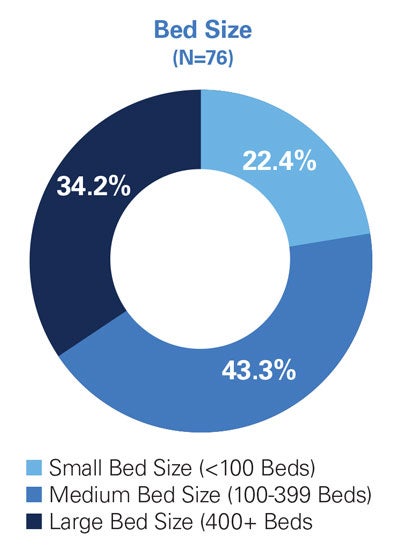

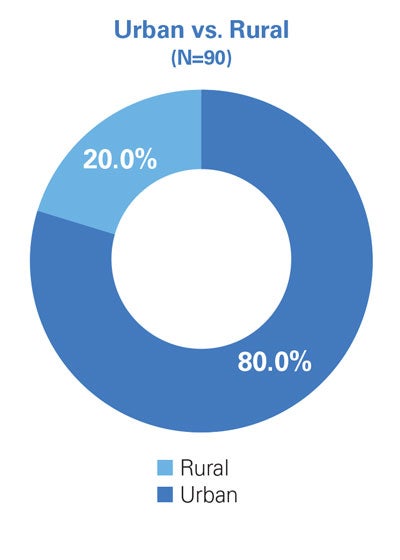

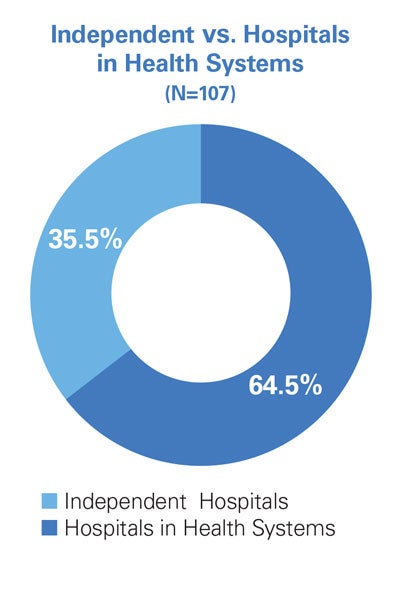

Final Survey Respondent Demographics (N=158)

Key Informant Interviews and Focus Groups

Interviews and focus groups were conducted between March and April 2022 to learn more about suicide prevention programs that hospitals and systems are implementing, as well as the challenges and barriers encountered in these areas. Focus groups were held on the topics of peer-to-peer support; and the use of EAPs. Additionally, one-on-one interviews were held with eight hospitals/health systems. Key informants were selected from the survey respondents based on several factors, including unique approaches to suicide prevention, programs offered at rural hospitals, and programs that integrated suicide prevention with diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Participants agreed that health care workers are most likely to seek out behavioral health and well-being services when they are accessible (via both on- and off-site care options), affordable, convenient and anonymous. Moreover, respondents also indicated that equipping health care workers with adequate mental health response training (e.g., Mental Health First Aid and Psychological First Aid) and promoting mental health awareness campaigns reduces the stigma of care-seeking behaviors and creates a culture of advocacy for treating mental health and preventing suicide. Finally, respondents agreed that collecting and monitoring data are critical to creating tailored and effective programs that support mental well-being and prevent suicide.

While these findings are not generalizable due to the small sample size, the interviews and focus groups provided input on mental well-being and suicide prevention programs from various types of hospitals and health systems. Refer to Appendix X for interview and focus group protocols, as well as a full list of hospitals and health systems who participated in the interview and focus group process.

Key Findings

Qualitative and quantitative analyses of the survey, key informant interviews and focus groups, and the literature review identified three primary drivers of suicidal behaviors for the health care workforce, shown in Figure 1.

Primary Drivers of Suicide in the Health Care Workforce - Figure 1.

Driver Stigma associated with talking about and seeking behavioral health care

- Fear from clinicians that seeking care may have a detrimental effect on their ability to renew or retain their state medical license

- Fear of losing hospital privileges via the credientialing process

- Fear of being perceived as "weak" or unable to perform on the job

- Feeling of being judged or unsupported by peers, managers, and/or senior leadership for seeking behavioral health care

- Fears about treatment confidentiality, especially when care is accessed at or provided by clinicians practicing at the same hospital or health system as the person receiving care

Driver Inadequate access to behavioral health education, resources, and treatment options

- Long wait times between referrals and starting care

- Behavioral health providers in the employee's health not having convenient office hours that accomodate a health care worker's schedule

- Out-of-pocket expenses for treatment exceeding the individual's ability to pay for care Uncertainty about how to access free resources from the EAP or Human Resources

Driver Job-related stressors

- Repeated exposure to death and dying

- Workplace violence

- Emotionally draining work

- Lack of support that acknowledges human limitations in a time of extreme work hours, uncertainty, and intense exposure to critically ill patients

- Lack of appropriate rewards (financial, social or intrinsic)

- Lack of connection with others in the workplace

- Lack of perceived fairness and mutual respect

- Mismatch between personal values and leadership/organizational values or organizational values and actual practice

- Insufficient control over resources needed or insufficient authority to pursue work more effectively

The three drivers were informed by both evidence-based practices and emerging practices identified by the literature review, as well as practices being employed by hospitals and health systems as reported in the surveys, key informant interviews, and focus groups.

While the literature review did not reveal any one specific intervention with strong evidence of preventing suicide among health care professionals, several interventions identified in the literature, survey data, and focus group and interview data demonstrated some indication of effectiveness, and a broad uptake among hospitals and health care systems. As the research community devotes more attention to this issue, hospitals and health care systems can introduce resources and support as a foundation for building evidence-based approaches and ensure that adequate, high- quality behavioral health and well-being and suicide prevention resources are offered.

Addressing the Drivers of Suicide in the Health Care Workforce - Figure 2.

Driver - Take Action Destigmatize Help-Seeking and Treament-Seeking Behaviors

- Create awareness and improve understanding about the prevalence of behavioral health disorders

- Create a culture of transparency where all employees feel safe to discuss behavioral health without fear

- Improve employee and medical staff capacity to respond to peers experiencing behavioral health concerns

- Eliminate credentialing questions and policies that stigmatize seeking behavioral health treatment or resources

Driver - Take Action Improve Access to Behavioral Health and Well-Being Resources

- Provide employees and medical staff with multiple options to pursue behavioral health services and screenings (on-site, off-site, and virtually)

- Ensure that employees and medical staff know how to access existing resources such as the EAP, behavioral health services covered by health plans, and other related resources

- Employ dedicated personnel to implement processes that oversee behavioral health and wellbeing resources

- Offer peer-to-peer support training and encourage engagement in peer support programming

Driver - Take Action Mitigating the Effects of Job-Related Stressors

- Continually examine the appropriateness of existing behavioral health and wellbeing programming

- Improve psychological safety through debriefing sentinel and emotional events in a non-punitive manner

- Provide support for addressing immediate concerns such as staffing shortages, burnout, and stress management

- Commit to providing employees and medical staff with culturally appropriate behavioral health treatment and resource options

High Priority Interventions and Metrics

These 12 evidence-informed interventions can be used to establish or expand a hospital or health system’s suicide prevention programming, and the associated metrics can be used to track progress toward the organization’s goals. Each intervention and metric correspond with at least one of the three key drivers of suicide in the health care workforce. These interventions and metrics are not a one-size-fits-all approach. Choose the interventions and metrics that work for your organization based on your hospital’s available resources to create a customized program to suicide prevention in the health care workforce.

Knowing where to start can often be overwhelming. Use the questions below to prioritize the interventions most appropriate for your organization.

Identifying and Prioritizing Interventions for Your Organization

- Inventory the suicide prevention, behavioral health and well-being tools already available at your organization. Identify what offerings are available at the individual level, the unit or department level, and at the organizational level.

- Quantify current program use, value and success, where possible.

- Identify any data sources for understanding the current state of suicide prevention, behavioral health, and well-being programming. This could be well-being or employee engagement survey data, specific program evaluations, or other existing data to provide clarity on what is needed to support the workforce.

Seven Questions to Ask For Each Intervention

- Who will lead and champion the implementation, and which stakeholders need to get involved?

- What internal resources, both staff and financial, will be required?

- What external resources are necessary?

- What is the anticipated timeframe anticipated tofor launching each intervention?

- How do you gain buy-in from the workforce for these initiatives?

- What are the anticipated barriers to implementation and how can they be overcome?

- How do you evaluate progress and scale up the program?

Leaders should implement these interventions with accompanying metrics and evaluate the effectiveness of the programs over time. The table below lists examples of metrics that demonstrate program uptake and efficiency, andefficiency and are informed by recommendations by the resources listed.

Explore More

Video

Learn more about how CHI & Common Spirit are reducing behavioral health stigma across their system.

Podcast

Learn more about how Providence Health has used interventions like the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention’s Interactive Screening Program tool to improve access to behavioral health screening, treatment, and resources.

Podcast

Learn more about how Linden Oaks Behavioral Health has committed to reducing and removing job-related stressors for their workforce.

Areas of Focus Interventions, Drivers, Metrics and Resources

A robust suicide prevention program should incorporate interventions that address all three drivers. The interventions are categorized into four types, according to their area of focus:

Increasing Access To Services

Intervention

Engage all hospital employees in an on-demand, anonymous and encrypted screening and referral program for behavioral health disorders

Example Protocols

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention Interactive Screening Program

- UC San Diego Healer Education Assessment and Referral (HEAR) Program

Key Drivers Addressed

■ Stigma ■ Access

KEY METRICS

- % of employees who participate in screening within a defined time period

- % of employees who receive referrals for treatment among those who screen as high risk

Intervention

Offer on-demand behavioral health resources and flexible treatment options to employees, medical staff and their families

Resources

For more information related to access to behavioral health care via health plans, view the AHA Workforce Navigation Guide.

Key Drivers Addressed

■ Access

KEY METRICS

- % of employees who utilize the organization’s EAP

- % of employees who indicate satisfaction with the EAP services provided

- # of referrals received by EAP program within a defined time period

- Average # of days between initial EAP contact and beginning treatment

Intervention

Ensure that licensed behavioral health clinicians who provide care to employees are trained to provide culturally appropriate mental health care

For More Information

- Cultural Diversity and Mental Health: Considerations for Policy and Practice (2018)

- AHA Health Equity Roadmap

Key Drivers Addressed

■ Stigma ■ Access

KEY METRICS

- % of behavioral health providers completing cultural competency training

Suggestions for Future Work

For Researchers

- While there are certain age and identity factors that put people in the general population at a higher risk for suicide, such as being between ages 45-54, identifying as LGBTQ+, and identifying as male (SAMHSA, 2022), more research is needed to understand whether being a health care worker who also falls into one of those categories increases the risk for suicide.

- There is limited research available on suicide prevention approaches for health care workers who work in non-clinical positions (e.g., environmental services, administrators, security, patient advocates, etc.). Most of the available research focuses on specific clinical roles such as physicians or nurses rather than on the health care workforce overall, and there is an opportunity to expand understanding in this area.

- Limited research exists on the effectiveness of health care worker suicide prevention initiatives at rural and critical access hospitals. As people who live in rural areas typically have more limited access to behavioral health care and have a higher risk for suicide than those who live in urban areas (CDC, 2022), there is a need to understand the efficacy of suicide prevention programs in this setting.

- Current research on suicide in the hospital and health system workforce shows that women in medicine have a greater risk of suicide compared to women in other occupations. More research is needed to gain clarity on the risk factors, and accordingly effective interventions.

For Hospitals and Health Systems

- Build or enhance suicide prevention, behavioral health and well-being programming, focusing on the above interventions.

- Identify groups of employees who are statistically most at risk for suicidality and target interventions for these groups.

- Have a plan in place to offer postvention services to all employees in the event of a suicide.

For Hospital and Health Care Associations

- As organizations begin to consider implementing their own programs relating to suicide prevention, convene hospital leaders to share knowledge and concerns, problem solve, and co-create tools and resources.

- Expand awareness of existing evidence-informed interventions to the 5,000+ American hospitals and health systems.

- Employ campaigns and interventions to reduce the stigma of seeking care for behavioral health.

Glossary

-

Behavioral health disorders include both mental illness and substance use disorders. Mental illnesses are specific, diagnosable disorders characterized by intense alterations in thinking, mood and/or behavior over time. Substance use disorders are conditions resulting from the inappropriate use of alcohol or drugs, including medications. Persons with behavioral health care needs may suffer from either or both types of conditions as well as physical co-morbidities.

-

Practices, methods, interventions, procedures, and techniques that are based on high-quality scientific evidence and proven improvement in outcomes (Ham-Bayoli et. al, 2020).

-

An evidence-informed approach blends knowledge from research, practice and people experiencing the practice. (Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2022)

-

An activity, procedure, approach, or policy that leads to, or is likely to lead to, improved outcomes (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2022).

The American Hospital Association would like to thank Dr. Judy E. Davidson DNP, RN, MCCM, FAAN, University of California San Diego, and Katherine J. Gold, MD, MSW, MS, University of Michigan, for their contributions to the creation of this guide.

Development of this product was supported by Cooperative Agreement CK20-2003, funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of CDC or the Department of Health and Human Services.