AHA Urges MedPAC to Consider the Current Financial Challenges Faced by Hospitals and Health Systems

November 30, 2022

Michael Chernew, Ph.D.

Chairman

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission

425 I Street, NW, Suite 701

Washington, D.C. 20001

Dear Dr. Chernew:

On behalf of our nearly 5,000 member hospitals, health systems and other health care organizations; our clinician partners — including more than 270,000 affiliated physicians, 2 million nurses and other caregivers — and the 43,000 health care leaders who belong to our professional membership groups, the American Hospital Association (AHA) appreciates the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission’s (MedPAC) continued discussions on its safety-net proposal, payment alignment across ambulatory settings and payments to primary care clinicians. As the Commission continues its deliberations, we would like to share our thoughts, suggestions and concerns related to these issues.

Additionally, as MedPAC begins its discussions on payment adequacy for the Medicare program, we urge the Commission to carefully consider the current economic and financial challenges faced by hospitals and health systems. Additional support for payment updates is urgently needed.

Therefore, we encourage the Commission to consider the following concerns and recommendations, each of which is discussed in more detail below:

- A one-time retrospective adjustment to be added to the fiscal year (FY) 2024 payment update to help hospitals and health systems remain financially viable.

- Implications of the Commission’s safety net proposal on the greater ecosystem of safety net funding.

- Concerns related to alignment of payment rates across ambulatory settings, especially given the sustained hardship hospitals would experience under these very large cuts.

- The impact on existing shortages and disparities in the specialty care space if the Commission’s proposals on primary care payments were to advance under budget neutral provisions.

Our detailed comments on these issues follow.

Download the complete letter PDF.

Hospital Payment Update

The current inflationary economy and ongoing workforce challenges have put unprecedented pressure on America’s hospitals and health systems. Health care providers continue to struggle with persistently higher costs and additional downstream challenges that have emerged because of the lasting and durable impacts of high inflation and the pandemic. We urge MedPAC to consider these dynamics on Medicare payment updates for FY 2024.

Generally, to make payment updates to the various fee-for-service Medicare payment systems, CMS uses the market basket to account for price inflation measures that impact the provision of medical services.1 However, the FY 2022 payment updates hospitals received failed to account for numerous and unexpected price increases that occurred later in the year, such as those due to general economy-wide inflation and expense pressures from workforce shortages. This is because the market basket is a time-lagged estimate that is based on historical data. When historical data vastly underestimate future inflation, the market basket becomes inadequate. Specifically, the general economy-wide inflation ranged from 6.2% to 9.1% during FY 2022 while inpatient prospective payment system (PPS) hospitals received a market basket update of 2.7% and long-term care hospitals (LTCHs) received an update of 2.6% during the same time period. Therefore, to support hospitals and health systems with their ongoing financial challenges, we urge MedPAC to recommend a one-time retrospective adjustment be added to the FY 2024 market basket updates for these providers, which would account for the difference in what hospitals should have received and what they did receive in FY 2022.

Current Context

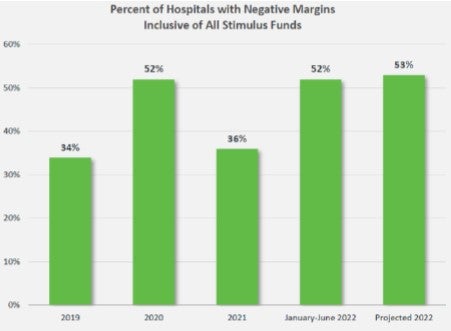

The financial pressures providers are experiencing are massive. Expenses continue to rise across the board, with hospitals facing increasing costs for labor, drugs, purchased services, personal protective equipment (PPE), and other medical and safety supplies needed to care for patients. An April 2022 report by the AHA highlights the significant cost growth in hospital expenses across labor, drugs and supplies, as well as the impact that rising inflation is having on hospital prices. By the end of calendar year 2021, total hospital expenses per adjusted discharge were up 20.1% compared to pre-pandemic levels in 2019. Moreover, total hospital expenses are projected to increase by $135 billion in 2022 compared to 2021, based on a more recent report published in September 2022. As the graph below demonstrates (reproduced from the report), more than half of hospitals are projected to close the year with negative operating margins, the highest proportion in recent years. Among other implications, this has resulted in credit rating agency Fitch Rating to revise its mid-year 2022 outlook to “deteriorating” for the nonprofit hospital sector due to “more severe-than-expected macro headwinds.”

Our members report similar increases in expenses. Specifically, one reported that from the first quarter of calendar year 2019 to the first quarter of calendar year 2022, salaries across their LTCHs rose by 35% for registered nurses, 46% for nurse aides and 39% for respiratory therapists. Overall, their labor costs during this time period rose by 27%. Another of our LTCH members reported that during the same time period, salaries rose by 56% for registered nurses, 39% for licensed practical nurses and certified nursing assistants, and 31% for respiratory therapists.

Additionally, hospitals continue to face additional financial pressures from major difficulties in discharging patients to the appropriate care setting. Our members have attributed the increased length of stay to several factors, including “patient acuity, delays in discharge due to insurance approvals required for post-acute inpatient care and bed availability in the post-acute facilities due to staffing shortages.”2 This means patients must remain in beds longer than is medically necessary, and as a result, hospitals bear the costs of care for those excess days generally without any additional reimbursement.

Indeed, these challenges are evidenced by recent data. Average lengths of stay have increased 10% in 2021 compared to pre-pandemic levels.3 In addition, a recent Modern Healthcare article highlighted data from health care technology company WellSky, which analyzed data from federal agencies, 1,000 hospitals and 130,000 post-acute care providers on referral rejection rates. These rates measure how often post-acute care facilities deny admission to patients being discharged from the hospital. In the first quarter of 2022, the rejection rate in skilled-nursing facilities was 88%. For home health providers, the rate increased from 49% in the second quarter of 2020 to 71% in the second quarter of 2022.

In addition to hospitals and health systems facing these acute challenges, they must continue to navigate in environments where Medicare persistently pays substantially less than the costs of care. Indeed, Medicare only pays 84% of hospital costs on average according to our latest analysis.4 In fact, according to MedPAC itself, in 2020, Medicare payments were less than the cost of care for two-thirds of hospitals and overall Medicare margins for inpatient PPS hospitals fell to negative 12.6% without COVID-19 relief funds.5 Overall Medicare margins for LTCHs were less than the cost of care from 2017 through 2019, but reached 3.6% in 2020, solely due to temporary, public health emergency-related increased payments. Indeed, MedPAC estimated that Medicare margins will remain depressed throughout 2021 and 2022, ranging from negative 6% to negative 10% for inpatient PPS hospitals. However, we are concerned that this is an overly positive outlook, given the information discussed above, as well as the ending of COVID-19 relief funds. In addition, MedPAC estimated that 2020 Medicare margins for inpatient PPS hospitals would be negative 8%; however, they were actually negative 12.6% — a 4.6% difference. This was the highest deviation in estimated versus actual Medicare margins for the past decade and speaks to the difficulty in understanding the temporary and lasting impacts of inflationary and pandemic challenges on current hospital finances. Finally, as we detail later in this letter, MedPAC’s proposals related to safety-net and payment rates across ambulatory settings would further erode hospital payments and the degree to which they cover costs. A margin that both covers costs and is adequate for capitalization is critical to allow hospitals to continue providing services. Negative margins, let alone those in the realm of negative 12.6%, are not acceptable as such.

FY 2022 Hospital Payment Update

Appropriately accounting for recent and future trends in inflationary pressures and cost increases in the hospital payment updates is essential to ensure that Medicare payments for hospital services more accurately reflect the cost of providing care. However, the FY 2022 hospital payment updates failed to do so. For FY 2022, CMS finalized a market basket of 2.7% for inpatient PPS hospitals. Similarly, CMS finalized a market basket of 2.6% for LTCHs. To do so, it forecasted by using estimates from historical data through the first quarter of calendar year 2021.6 Because this market basket was a forecast of what was expected to occur, it missed the unexpected trends that did occur in the latter half of FY 2022.

Specifically, as we detailed extensively in our comment letters on the inpatient PPS and LTCH proposed rules to CMS, these unexpected trends include high inflation, which began to take hold in the second half of calendar year 2021, with the consumer price index (CPI) ultimately hitting a 12-month high in June 2022 at 9.1%.7 The market baskets also failed to account for skyrocketing labor expenses, which are projected to grow by $86 billion in 2022.8 Additionally, elevated patient acuity continues to contribute to increased costs. The case mix index for Medicare FFS inpatient has risen 7% in 2021 compared to 2019, according to an August 2022 report by Kaufman Hall.

Using historical data to forecast into the future ultimately resulted in FY 2022 payment updates that failed to account for unexpected price inflation that occurred later in the year. Indeed, as more recent data become available beyond those used to forecast the FY 2022 market baskets,9 the inpatient PPS market basket is trending toward 5.5% — a full 2.8% higher than the 2.7% CMS implemented. Similarly, the LTCH market basket is trending toward 5.3% – a full 2.7% higher than what CMS implemented. We urge MedPAC to recommend one-time retrospective adjustments be added to the FY 2024 inpatient PPS and LTCH market basket updates to account for the difference between what hospitals should have received and what they did receive in FY 2022. Specifically, this adjustment would currently be the 2.8% referenced above for inpatient PPS hospitals and 2.7% for LTCHs.

Support for Safety-Net Providers

At the November 2022 meeting, MedPAC staff presented follow-up analyses to their June 2022 report chapter, “Supporting safety-net providers.” This presentation included analysis and discussion of using a “safety-net index” (SNI) to target Medicare payments to hospitals and health systems that treat the most low-income Medicare beneficiaries. Commissioners had a robust discussion of the financial pressures that many safety-net providers face and of Medicare’s role in the nation’s health system.

We appreciate the Commission’s thought leadership for identifying ways to help these hospitals that serve vulnerable patients and provide critical services. The AHA has also been examining this critical issue of how better to support urban hospitals that provide critical care and social services to vulnerable patients who are low-income and often experience challenges in accessing care. Thus, the AHA urges the Commission to consider an alternative approach to supporting safety-net providers, as outlined below.

We consider these urban hospitals that care for patients in low-income or historically marginalized communities to be Metropolitan Anchor Hospitals (MAH) because of the anchor role they play in their communities. Specifically, we believe Congress should establish a MAH designation in statute for hospitals that meet the criteria we have outlined, which includes geographic and uncompensated care costs, among others. In addition to being a key access point for many kinds of care, they also serve as de facto public health entities within their communities. Additionally, to address the urgent unmet needs of their patients, they often develop and lead social support programs such as transportation services, on-site childcare, nutrition services, charity programs and public health awareness campaigns that benefit the broader community.

According to our analysis, hospitals that meet these criteria — MAHs * are more likely to provide essential services, such as burn care, neonatal intensive care, trauma care and HIV/AIDS support. They are more likely to provide care for patients who face health inequities, structural and financial barriers, and other challenges in accessing timely, culturally competent and high-quality care. These hospitals also provide a wide variety of services to a disproportionate number of patients who are insured by Medicaid or Medicare, or are uninsured, and they deliver a significant amount of uncompensated care or charity care. MAHs also devote significant resources to addressing the social determinants of health (SDOH) in the communities they serve. To help meet individuals’ health-related socio-economic needs, MAHs often work to address housing needs, food insecurity, nutritional counseling and transportation to care.

More information about who would qualify, what types of patients they serve, and what clinical and non-clinical services they provide can be found in NORC’s research paper, “Exploring Metropolitan Anchor Hospitals and the Communities They Serve.”

MedPAC Safety Net Index

The AHA thanks the Commission for recognizing that more can and should be done to support the sustainability of these critical hospitals and health systems and urges the Commission to consider the above alternative approach. Related to MedPAC’s own safety-net index proposal, we urge the Commission to recommend the use of new funds to support safety-net providers, rather than redistributing existing Medicare DSH and uncompensated care funds. Medicare DSH and uncompensated care payments are intended to bridge the gap between the cost of providing care to certain patients and low Medicare payment rates. As documented above, inflation and costs have skyrocketed in 2022, making this one of the most financially challenging years for hospitals since the pandemic began and only exacerbating this gap. Reducing revenue to hospitals that score low on the safety-next index will have significant implications for Medicare beneficiaries and other patients at these hospitals. Support for safety-net hospitals should not come at the expense of other Medicare beneficiaries and other patients.

In addition, we urge the Commission to increase transparency around their proposal. The Commission has discussed at the aggregate level the types of hospitals that would benefit or be disadvantaged by this proposal, but there are still unanswered questions about how specific hospitals may be affected. At the November meeting, several commissioners, including Ms. Barr and Dr. Riley, expressed concern that this proposal would adversely affect large county or other public hospitals. These concerns should be addressed by making the commissions’ analysis of the SNI public, so that commissioners and the public are better informed about how hospitals and health systems would be affected by the proposal. The Commission has also discussed the SNI at a conceptual level, including the three components on which it is derived, but many questions remain about the specific methodology used to arrive at an individual hospital’s SNI score. For example, what data sources the Commission uses to calculate the SNI (including what data source is used to identify low-income Medicare beneficiaries), and how Medicare Advantage is accounted for in the Commission’s analysis. Making the methodology more transparent would allow others to model the proposal and could better inform future policy discussions.

We also urge the Commission to consider and discuss the implications of this proposal in greater depth. The Commission’s discussion seemed to focus on financial margins and hospital closures as the primary metrics by which to evaluate the merits of the proposal. These are important measures, but this policy may have other implications for hospitals and Medicare beneficiaries. For example, the Commission should consider what implications this proposal may have for service-line closures, hospitals’ investments in new technology or upgrades to their facilities, and hospitals’ ability to access capital. By reducing payments to hospitals with low SNI scores, this proposal could inadvertently create or exacerbate financial pressures for hospitals and health systems who provide care for Medicare beneficiaries and other patients. Several of the commissioners expressed the desire to continue this conversation in more detail. For example, Dr. Jaffrey expressed concern about the impact of the proposal on hospitals in the lowest quartile, noting that it “really does feels substantial.”

Finally, we ask the Commission to reconsider whether Medicare payment policy is cross-subsidizing other programs. During the commission’s discussion, staff and commissioners expressed concern that Medicare DSH payments were indirectly subsidizing hospitals for providing care to Medicaid and uninsured patients. In 2020, Medicare paid 84 cents for every dollar spent caring for Medicare beneficiaries, resulting in an estimated $75.6 billion shortfall. According to Commission’s analysis, overall Medicare margins were negative 12.6% (not including relief funds). It seems unlikely that any institution could cross-subsidize care based on rates that do not cover the cost of providing care.

We ask that the Commission consider that Medicare DSH creates incentive for hospitals and health systems to provide care for patients regardless of what type of coverage they carry, or their ability to pay. Medicare DSH payments reimburse hospitals for providing care to patients who are often described as vulnerable, which typically means they lack access to care, have difficulty affording health care and other needs, have complex health needs, or face unmet health and social needs. Many of these patients face health disparities and other inequities. Redefining safety-net to mean hospitals that serve a large share of only low-income Medicare beneficiaries could create new incentives for hospital to focus exclusively on certain patients. This could further exacerbate inequities that many of these hospitals are working hard to eliminate.

The Commission engaged in a rich and interesting philosophical conversation around the purpose of Medicare, and whether Medicare funding should only be spent on Medicare beneficiaries. Several commissioners, including Dr. Casalino, raised questions about whether the Commission was applying this philosophy consistently across MedPAC’s policy discussions. This is an important question, as Medicare is often used as a policy lever to encourage providers to do something that benefits all patients. For example:

- Some Medicare quality measurement programs ask hospitals to report data on an all-payer basis, such that Medicare funding is used to encourage providers to improve quality for all patients.

- One of the most important conditions of participation for Medicare is that hospitals must protect and promote each patient’s rights, regardless of their coverage. Policymakers made the decision that this right for all patients is so important that it was worth connecting to participation in the Medicare program.

- Medicare also funds a portion of federal graduate medical education training to help train the next generation of providers to care for all patients. These payments help fund infrastructure investments, residents’ stipends, salaries for faculty that oversee residents, and resident and faculty benefits.

Alignment of Payment Rates across Ambulatory Settings

At the November meeting, Commissioners again discussed an approach to establishing site-neutral payment rates across ambulatory settings. Under this approach, payments for certain services currently paid under the OPPS would be reduced either to the residual difference between the physician fee schedule (PFS) nonfacility and facility practice expense (PE) payment or to the ambulatory surgical center (ASC) payment rate, depending on the setting in which the particular service was furnished the majority of the time.

MedPAC staff stated that hospitals’ overall Medicare revenue would decrease by 4.5% under these policies. However, the impact would be greatest for rural hospitals and government hospitals, which would see the highest percent decrease — 7.6% and 5.3% respectively. To temporarily reduce the impacts of the cuts on certain safety net hospitals, the Commission discussed applying stop-loss policies. However, even with a temporary stop-loss policy, these hospitals would experience substantial cuts in overall Medicare revenue — 5.8% and 3.9% respectively. These cuts would be made on top of the negative 12.6% Medicare margin MedPAC calculated for hospitals for 2020.

The AHA continues to strongly oppose site-neutral cuts. As we discussed in our Dec. 2, 2021 letter to the Commission, these proposals would be devastating, particularly to rural and other hospitals that serve patients and communities with sustained hardship. Existing site-neutral payment policies have already been a significant blow to hospital financial stability, particularly about the COVID-19 pandemic and the other challenges that threaten hospitals’ ability to care for patients and provide essential services for their communities. As we have detailed extensively above, for many hospitals and health systems, continued financial viability is becoming increasingly difficult as they manage the aftermath of the most significant public health crisis in a century, as well as the incredible challenges of deepening workforce shortages, broken supply chains and historic levels of inflation that have increased the costs of caring for patients. Now more than ever, hospitals need stable and adequate government reimbursements for what is a highly challenging environment.

As discussed in our letter Dec. 2, 2021, the AHA conducted an analysis of the impact that the proposed site-neutral policies would have on hospitals’ Medicare margins. The results show the devastating impact of these policies on hospitals’ total and outpatient margins, particularly on rural and government-owned hospitals, as shown in the tables below.

Table 1: Medicare Total Margins

| Hospital Type | Actual Medicare Total Margin, FY 2019 | Simulated Medicare Total Margin, MedPAC Proposed Site-neutral Policy | Simulated Medicare Total Margin, MedPAC Proposed Site-neutral Policy, including Stop-loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Hospitals | -8.4% | -13.5% | -12.7% |

| Urban | -8.3% | -13.1% | -12.3% |

| Rural | -24.2% | -34.5% | -31.9% |

| Nonprofit | -8.5% | -13.8% | -12.9% |

| For Profit | -1.7% | -5.2% | -5.0% |

| Government | -20.7% | -27.4% | -25.6% |

The impacts on Medicare outpatient margins would be even more devastating. Rural hospitals’ outpatient margins would decline from negative 28.2% to negative 64.1%. Government-owned hospitals’ outpatient margins would decline from negative 27% to negative 51.7%.

Table 2: Medicare Outpatient Margins

| Hospital Type | Actual Medicare Outpatient Margin, FY 2019 | Simulated Medicare Outpatient Margin, MedPAC Proposed Site-neutral Policy | Simulated Medicare Outpatient Margin, MedPAC Proposed Site-neutral Policy, including Stop-loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Hospitals | -15.5% | -35.4% | -31.7% |

| Urban | -15.4% | -34.2% | -30.5% |

| Rural | -28.2% | -64.1% | -53.6% |

| Nonprofit | -16.4% | -36.2% | -32.2% |

| For Profit | -6.7% | -22.5% | -21.4% |

| Government | -27.0% | -51.7% | -44.0% |

Cuts of these magnitudes cannot be sustained. For better or worse, the hospital safety-net and emergency stand-by role are funded through the provision of all outpatient services. Expanding site-neutral cuts to the degree discussed by MedPAC, on top of the financial impacts U.S. hospitals and health systems have faced due to COVID-19 and the current financial crisis, would endanger the critical role that hospital-based outpatient departments (HOPDs) play in their communities, as well as access to care for beneficiaries, including the most medically complex.

And it appears that several MedPAC commissioners have similar concerns. We note that although MedPAC staff at the November meeting said that these proposed site neutral policies represented a consensus among commissioners, during the discussion it became clear that some commissioners were not supportive, or at least were uncertain whether moving forward with a recommendation this coming spring would be appropriate.

One commissioner was “vehemently opposed” to this proposal, noting “now is not the time to be messing around with these types of things, and we’ve got to let the whole COVID thing sort out and inflation thing sort out […] and this is just not the time. But, you know, more specifically, a 5% hit on rural? I mean, how many more hospitals do we want to close? […] Anything that’s going to threaten sort of the whole system right now I think is a very bad idea.” Another commissioner, while generally supporting moving forward, said, “I don't think now is the time to take dollars out of the hospital sector of the industry. I think there's still a lot of re-equilibrating that's yet to happen.” Yet other commissioners, while supporting the overall policy direction expressed concern about possible unintended effects and urged taking time to “get the incentives right” prior to proceeding with a recommendation.

The AHA urges MedPAC to listen to these words of caution from commissioners and abandon further recommendations regarding site-neutral payment policies.

Medicare Payments to Primary Care Clinicians

At the November MedPAC meeting, we appreciated the Commission’s report and presentation on policy options to increase Medicare payments to primary care clinicians. Specifically, we appreciated the overview of the continuing challenges in recruiting and retaining primary care physicians, and factors contributing to the decline in the number of primary care physicians billing for services (such as compensation disparities compared to specialty care).

The solutions provided focused on how to update the E/M coding structure to increase reimbursement for primary care physicians either 1) via a separate E/M service fee schedule, or 2) through a per patient per month primary care capitated model.

The AHA acknowledges the impact of reimbursement, compensation potential and workload credit in incentivizing potential physicians to select primary care for their careers. However, the AHA has concerns on the policy options presented to address Medicare payments to primary care clinicians, particularly if these options are going to be advanced under the same budget neutrality provisions as historical payment rate modifications. For example, using specialty care payment reductions to fund additional primary care physician reimbursement may exacerbate existing shortages in the specialty care space and could in fact make certain disparities worse (e.g., oncologists in rural or underserved areas). In many cases, these specialists are managing care and fulfilling primary care functions. This is especially concerning in the current environment in which the physician fee schedule will see a cut of almost 4.5% come Jan. 1, 2023.

Additionally, the full impact of the changes to E/M coding structure implemented in the CY 2021 Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule (including migrating to coding based on total time or medical decision making) is still being determined. A study from University of Chicago10 showed that time-based E/M coding may increase revenue potential for physicians with longer patient visits, however a separate study from American Association of Professional Coders11 showed that coding compliance is around 81% compared to 91% prior to when the updated guidelines were published. These suggest that additional time may be needed to optimize existing E/M coding structure before introducing further modifications, and similar to previous comment letters to CMS, we urge the agency to consider the degree of redistribution among specialties that these proposals could create. Therefore, we instead encourage a comprehensive set of policy solutions that include evaluating the broader scope of staffing needs and adopting solutions to support team-based care, expanding the number of GME slots, and improving coding compliance and updating workload calculations, as well as supporting other policy areas like making permanent telehealth waivers to better support workforce capacity management.

Addressing the Broader Healthcare Worker Shortage Crisis

While we appreciate the commission’s focus on primary care shortages, practices, hospitals and health systems are struggling with unprecedented shortages across both primary and specialty care.

A report from the Association of American Medical Colleges12 released in June of last year updated projections from 2019 to 2034, which showed demand continuing to outpace supply for clinicians across both primary and specialty care. In fact, AAMC estimates a shortage of between 17,800-48,000 primary care physicians and 21,000-77,100 non-primary care specialty physicians by 2034. This is primarily driven by the general population growth and aging of the population, the proportion of clinicians approaching retirement, and the impact of COVID-19 on practice and burnout. In addition, the AAMC projects that if certain population health and health equity goals are met, the potential shortage of physicians would be even larger (between 102,400-180,400).

Hospitals’ ability to recruit and retain all types of physicians is being challenged by the financial pressures they face. Even before the pandemic, labor costs — including recruitment, retention, benefits, incentives and training — accounted for more than 50% of hospitals’ total expenses. By the end of 2021, hospitals’ labor expenses per patient were 19.1% higher than pre-pandemic levels, and as we have detailed above, are projected to grow even more in 2022 compared to 2021. The rising costs of labor have outpaced changes to reimbursement across the board.

Given the shortages in both primary and specialty care, the AHA strongly encourages solutions that are not zero sum in nature. We are concerned that budget neutral recommendations will have an adverse impact on specialty areas that are already experiencing shortages and to hospitals and health systems already operating at a loss. This could exacerbate existing disparities in access to specialty care for rural and underserved populations.

Additional Elements to Address

There are additional elements that we encourage the commission to address as it continues its deliberations on this issue. Specifically:

- What are the trends in non-physician billing and compensation for primary care settings (e.g., NP’s, PA’s, APN’s, RN’s etc.)? What incentive models can be established to better promote team-based care? The two options provided focused on reimbursement and compensation for primary care physicians, not incentives for the broader care team and how to appropriately leverage clinicians across different provider types to the maximum extent of their scope of practice. Additionally, as mentioned by several members of the commission, there continues to be a lack of current data to better support RVU adjustments (for work and practice expense).

- How can we increase the number of GME slots to better support a pipeline of physicians across settings? The purpose of GME funding is to ensure an adequate supply of well-trained physicians. Increasing the number of slots will help support a sustainable pipeline of physicians for both primary and specialty care.

- What are the impacts of COVID-19 and the E/M coding requirements published in 2021 on the billing and compensation information provided? Utilization patterns in ambulatory care were not only impacted by COVID-19 (and closures during quarantine) but also by updated coding guidelines that impacted E/M coding compliance. The E/M modifications made in 2021 were some of the most significant since E/M coding was first finalized in 1997. As such, there seems to still be continued challenges in coding compliance with the new requirements. According to an AAPC report13 looking at 300,000 records, overall coding accuracy was around 81% post-2021 compared to 91% pre-2021. One of the case studies highlighted post-implementation challenges in under-coding (particularly in specialty and pediatric practices). After multiple audits and education, there was improvement in rates of over- and under-coding, but still 14% of records were inaccurate. This shows that additional time is needed to implement existing updates to E/M coding before making additional changes.

- How has telehealth supported capacity during the PHE? MedPAC’s March 2022 report14 to Congress highlighted that telehealth utilization expanded substantially during the pandemic and utilization in primary care settings continues to be around 10%. Indeed, telehealth can be an effective way to provide access for geographically dispersed patient populations and manage limited capacity in provider shortage areas. As such, it would be helpful to also consider policy recommendations to make certain waiver provisions permanent, such as eliminating originating site restrictions.

- How many clinicians in non-primary care specialties are functioning as beneficiaries’ primary clinician and to what extent would they be compensated under new care management models? In many instances, specialty providers are performing primary care functions. In at least one of the options under consideration – option 2, which would establish a per patient per month primary care capitated model - does not seem to address how these providers would be included or compensated.

We thank you for your consideration of our comments. Please contact me if you have questions or feel free to have a member of your team contact Shannon Wu, AHA’s senior associate director of policy, at swu@aha.org or 202-626-2963.

Sincerely,

/s/

Ashley B. Thompson

Senior Vice President

Public Policy Analysis and Development

Cc: James E. Mathews, Ph.D.

MedPAC Commissioners

- CMS. (May 2022). “FAQ – Market Basket Definitions and General Information.” https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MedicareProgramRatesStats/Downloads/info.pdf

- AHA. (Oct 2022). Data Brief: Financial Challenges for Hospitals Persist Through 2022. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2022/10/data-brief-financial-challenges-for-hospitals-persist-through-2022.pdf

- AHA. (Oct 2022). Data Brief: Financial Challenges for Hospitals Persist Through 2022. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2022/10/data-brief-financial-challenges-for-hospitals-persist-through-2022.pdf

- American Hospital Association (February 2022). Underpayment by Medicare and Medicaid Fact Sheet. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2022/02/medicare-medicaid-underpayment-fact-sheet-current.pdf

- MedPAC. (2022). March 2022 Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Chapter 3 – Hospital inpatient and outpatient services. https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Mar22_MedPAC_ReportToCongress_SEC.pdf

- 86 Fed. Reg. 45214 (August 13, 2021).

- Statista. (Oct 17, 2022). Monthly 12-month Inflation Rate in the United States from Jan 2020 to Sep 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/273418/unadjusted-monthly-inflation-rate-in-the-us/

- AHA (Sep 15, 2022). Current State of Hospital Finances: Fall 2022 Update. https://www.aha.org/guidesreports/2022-09-15-current-state-hospital-finances-fall-2022-update

- IHS Global, Inc.’s (IGI’s) forecast of the IPPS market basket increase, which uses historical data through first quarter 2022 and second quarter 2022 forecast. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MedicareProgramRatesStats/MarketBasketData

- Mikansek, T., Edwards, S., Weyer, G. (August 31, 2022). “Association of Time-Based Billing With Evaluation and Management Revenue for Outpatient Visits.” https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2795796

- Scott, S. (March 31, 2022). “Study Shows Physicians and Medical Coders are Struggling with Accuracy Rates and Other Challenges.” https://www.aapc.com/blog/84470-looking-back-on-2021-e-m-changes/

- AAMC (June 2021). “The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2019 to 2034.” https://www.aamc.org/media/54681/download

- Scott, S. (March 31, 2022). “Study Shows Physicians and Medical Coders are Struggling with Accuracy Rates and Other Challenges.” https://www.aapc.com/blog/84470-looking-back-on-2021-e-m-changes/

- MedPAC. “March 2022 Report, Chapter 4: Physician and Other Health Professional Services.” https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Mar22_MedPAC_ReportToCongress_Ch4_v2_SEC.pdf