AHA to CMS Re: Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility PPS for FY 2023 and Updates to the IRF Quality Reporting Program

The Honorable Chiquita Brooks-LaSure

Administrator

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

Submitted electronically

Re: Medicare Program; Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Prospective Payment System for Federal Fiscal Year 2023 and Updates to the IRF Quality Reporting Program.

Dear Administrator Brooks-LaSure:

On behalf of our nearly 5,000 member hospitals, health systems and other health care organizations, including approximately 900 inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRF), and our clinician partners — more than 270,000 affiliated physicians, two million nurses and other caregivers — and the 43,000 health care leaders who belong to our professional membership groups, the American Hospital Association (AHA) appreciates the opportunity to address the FY 2023 IRF prospective payment system (PPS) proposed rule.

The AHA appreciates CMS’s streamlined proposed rule, which helps IRFs and their partners in surging areas continue to focus on their local COVID-19 responses. In addition, we continue to appreciate the IRF-related waivers implemented by CMS, which help optimize the field’s contribution to the national response, both in communities still experiencing surges, as well as for higher-acuity patients recovering from the virus who require both hospital-level care and intensive rehabilitation to address longer-term clinical after effects.

Proposed FY 2023 Payment Update Warrants Closer Examination

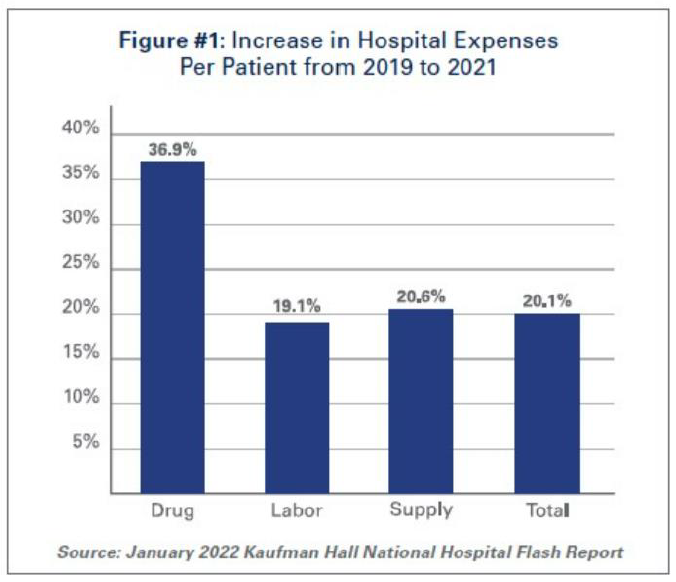

For FY 2023, CMS is proposing a net increase in IRF PPS payments of 2.0% ($170 million), relative to FY 2022. This includes a 3.2% market-basket update offset by a statutorily-mandated cut of 0.4 percentage points for productivity, and a 0.8 percentage point cut related to high-cost outlier payments. We note that the proposed IRF PPS labor-related share would only modestly shift upward from 72.9% in FY 2022 to 73.2% in FY 2022. AHA is concerned that these changes neither align with feedback from our members regarding massive cost growth in recent months and years, nor with the findings of recent AHA-commissioned research. Specifically, an April 2022 report by the AHA highlights the significant growth during the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE) in hospital expenses across labor, drugs, and supplies (as shown in the reproduced chart below), as well as the impact that rising inflation is having on hospital prices.

The report cites Bureau of Labor Statistics data showing that hospital employment levels have decreased by approximately 100,000 from pre-pandemic levels. At the same time, hospital labor expenses per patient through 2021 were 19.1% higher than pre-pandemic levels in 2019. Because labor costs account for more than 50% of hospitals’ total expenses, such increases have very substantial impacts on a hospital’s total expenses and operating margins. As widely reported, an increased reliance on contract staff, especially contract nurses, who are integral members of the clinical team, has been driving growth in labor expenses; in 2019, hospitals spent a median of 4.7% of their total nurse labor expenses on contract travel nurses, but by January 2022 this figure skyrocketed to a median of 38.6%.

As a result of these changes, January 2022 labor expenses per adjusted discharge are 52% higher than the pre-pandemic levels of January 2020. We are deeply concerned about increased costs to hospitals that are not reflected in the market basket adjustment and ask CMS to discuss in the final rule how the agency will account for these increased costs. We also are concerned about the reduction for productivity, and ask CMS in the final rule to further elaborate on the specific productivity gains that are the basis for the proposed 0.4% productivity offset to the market basket, as this does not align with hospitals’ PHE experiences related to actual losses in productivity during the pandemic.

Proposed Permanent Cap on Wage Index Decreases

The AHA supports CMS’s proposal to smooth year-to-year changes in the IRF PPS wage index. Specifically, to mitigate occasional fluctuations in year-to-year wage index changes, CMS proposes a permanent 5.0% cap on any decrease to a provider’s wage index, relative to the prior year, regardless of the circumstances causing the decline. We agree that such a cap would help maintain stability for this payment system, and the others for which CMS also is proposing this cap. While we endorse this proposed policy change, we urge the agency to implement this change in a non-budget-neutral manner. Only then would the proposed cap truly mitigate volatility caused by wage index shifts.

Adjustment for High-cost Outliers

The AHA is concerned about the dramatic scale of the proposed increase in the high-cost outlier threshold – a 37% increase from the FY 2022 threshold – that would significantly decrease the number of cases that qualify for an outlier payment. The agency’s proposed increase from $9,491 in FY 2022 to $13,038 in FY 2023 seeks to align total FY 2023 outlier payments with its target of 3% of total IRF payments. If the agency were to maintain the current threshold, CMS’s analysis of FY 2021 claims projects that outlier payments in FY 2023 would be 3.8% of total payments. This projection was calculated using the same methodology in effect since the FY 2002 implementation of the IRF PPS.

CMS’s long-standing goal in maintaining the 3% outlier pool, which is established in regulation only, is to allocate additional resources to high-need, higher-cost patients, without under-funding the remainder of IRF cases. That said, the proposed rule falls short by not explaining the factors driving this significant increase in IRF high-cost outlier payments, and CMS’s projection of the duration of these factors in FY 2023 and beyond. Furthermore, we are highly concerned about the methodology’s reliance on atypical FY 2021 claims.

As such, we ask CMS to examine its methodology more closely and consider making temporary changes, as it has done in other payment systems, to help mitigate substantial increases in the outlier thresholds. For example, in the inpatient PPS proposed rule, the agency used slightly older data to calculate the outlier threshold because CMS recognized that using the two most recent years produced abnormal results due to the pandemic.

Proposed Changes Regarding “Teaching IRFs”

AHA supports CMS’s proposals related to protocols for teaching IRFs. First, this rule would update the current policy addressing medical residents (and interns) who are displaced when a teaching IRF closes. Specifically, the rule would alter the status of a relocating resident based on the date that the originating IRF publicly announces its closure (for example, via a press release), rather than the actual closure date, which would mitigate delayed transfers of a displaced resident to a new IRF. In addition, the rule would allow the receiving IRF to increase its FTE resident cap by submitting a letter to its Medicare Administrative Contractor within 60 days after beginning to train the displaced residents.

Further, to improve clarity, CMS is proposing to codify and consolidate the definition of the teaching status payment adjustment factor, and explanation of how the factor is calculated, which is used for IRFs that provide graduate medical education. Specifically, CMS would codify in regulation guidelines that currently only are found in the Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Section 100-04, chapter 3, as they were established in FY 2006 final rule and modified in FY 2012 final rule.

Request for Information (RFI) on IRF Transfer Policy

AHA appreciates the opportunity to weigh in on CMS’s call for feedback from the field on whether to incorporate a “discharge to home health” element in the IRF transfer policy in the future, in alignment with inpatient and inpatient psychiatric facility PPS policies. The transfer policy is intended to disincentivize early discharges from IRFs. It currently applies to stays with a less than average length-of-stay for cases with comparable principal and secondary diagnoses, which are transferred directly to another IRF, general acute-care hospital, or nursing home/SNF. The rule cites a December 2021 report by the Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Inspector General report1 that found that this type of IRF transfer policy expansion would generate savings of approximately $1 billion over two years.

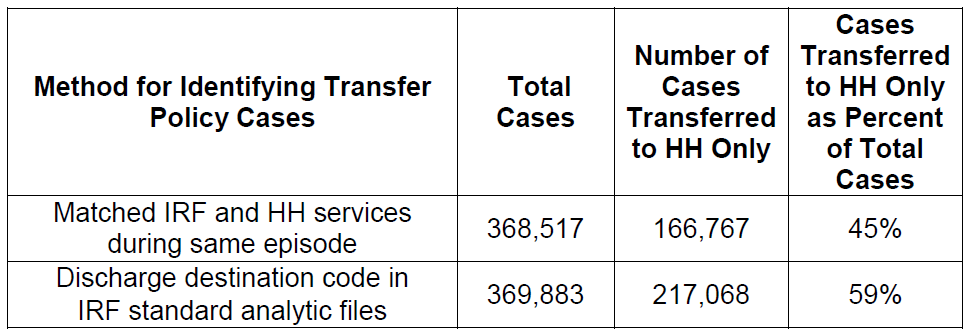

However, for any future consideration of a possible expansion of the IRF transfer policy, we recommend that CMS first evaluate the accuracy of the existing policy by confirming the reliability of the data currently being used to identify cases for a transfer policy payment reduction. To identify these cases, the policy uses “discharge destination code” data derived from the IRF-patient assessment instrument (PAI). We raise this concern based on an AHA analysis of CY 2021 standard analytic file (SAF) IRF claims that found the IRF-PAI-based discharge data appear to overstate, by 14%, the number of cases that actually are transferred from an IRF to home health. Specifically, as shown in the chart below, we found that 45% of IRF discharges actually receive home health services within three days, based on our claims-based analysis that matched beneficiary service utilization for IRF and then HH care during a single episode of care. However, using the discharge destination code on the CY 2021 SAF claims, we calculated a rate of 59%. Given this material inaccuracy, we urge CMS not to advance an expansion of this policy, as currently designed. Rather, CMS should evaluate whether and how much Medicare is penalizing IRF cases that actually comply with the policy. Any such over-payments should be corrected.

RFI on IRF PPS Facility Level Adjustments. While the rule proposes to maintain in FY 2023 the current IRF PPS facility-level payment adjustments listed below, CMS is asking for feedback on its methodology used to calculate facility-level adjustment factors and suggestion on possible refinements in the future. IRF PPS facility adjustments have been frozen since 2014 to mitigate the prior year-to-year volatility that persisted even following attempts by the agency to stem this source of instability. In general, the IRF field has supported this pause.

- Rural adjustment: 14.9%

- Low-income patient adjustment factor: 0.3177

- Teaching facility adjustment factor: 1.0163

The adjustments provide an increase in per-case payments based on an IRF’s rural status, percentage of low-income patients, and teaching status to account for differences in costs attributable to these characteristics. Prior annual updates were made in a budget-neutral manner, and any future changes also likely would be budget neutral.

While CMS is not proposing a change for FY 2023, the rule highlights what the annual facility adjustments would have been for FY 2015 through FY 2023, including substantial volatility. In other words, CMS’s freeze of the facility adjustments has helped increase payment predictability and stability for the field. Moving forward, we support CMS’s ongoing pursuit of a remedy to, absent the current freeze, mitigate the volatility that persists. In particular, we highlight members’ concerns with the accuracy of the teaching adjustment, and ask CMS to evaluate its reliability and impact, perhaps using the comparable inpatient PPS policy as a benchmark.

QUALITY REPORTING-RELATED PROPOSALS

IRF Quality Reporting Program (IRF QRP)

The Affordable Care Act mandated that reporting of quality measures for IRFs begin no later than FY 2014. Failure to comply with IRF QRP requirements results in a 2.0 percentage point reduction to the IRF’s annual market-basket update. For FY 2022, CMS requires the reporting of 18 quality measures by IRFs.

CMS does not propose to adopt any new quality measures or standardized patient assessment data elements (SPADEs) in this rule. The agency does propose to require IRFs to report quality data on all patients, regardless of whether they are Medicare beneficiaries. CMS also solicits comments on potential future measures for inclusion in the IRF QRP as well as on how the agency can leverage its programs to advance health equity.

Collection of Quality Data Regardless of Payer. Beginning Oct. 1, 2023, IRFs would be required to collect the IRF Patient Assessment Instrument (PAI) upon admission and discharge for each patient. CMS made the same proposal in the FY 2020 IRF PPS proposed rule, but did not finalize the proposal in response to several logistical questions raised in comments as well as assertions that the expansion and accompanying implementation timeline would be overly burdensome, especially considering the addition of several SPADEs to the IRF-PAI.

While CMS purports to have addressed these questions and assuaged these concerns, the AHA does not believe the information supporting this proposal bears this out. CMS argues that because providers currently report quality data on all patients in the Long-term Care Hospital (QRP) and the Hospice QRP, it is not unreasonable to expect IRF providers to do the same. The experiences of LTCHs and Hospices are not comparable to IRFs. According to MedPAC’s March 2021 Report to Congress, there were approximately 162,500 LTCH stays in 2019; in comparison, and according to the same report, there were over 705,000 IRF stays in the same year.

These vast differences in volumes demonstrate that expanding data collection for non-Medicare patients (who make up about 44% of those stays) is a significantly larger undertaking for IRFs than for LTCHs. Hospices currently do not administer a patient assessment in the same way as IRFs administer the PAI, but a comparable process is one by which hospices abstract data from medical records via a standardized tool called the Hospice Item Set (HIS). The HIS is 10 pages long; the IRF-PAI is 30. Again, the collection of data upon admission and discharge for additional patients in the hospice setting is not a comparable task in an IRF.

By CMS’s own calculations, each additional IRF-PAI would take 1.8 more hours of clinical staff time. The IRF workforce is already overburdened by administrative requirements, and as CMS adds more and more SPADEs to the IRF-PAI, there is less and less time for patient care. In addition, as approximately 44% of IRF patients are covered by commercial insurers, CMS should ensure that the assessment processes used for these payers are aligned with those informing the IRF-PAI so as not to introduce additional or conflicting processes. Because of the substantial increase in burden associated with this proposal, the AHA suggests that CMS extend the timeline for the implementation of this requirement until at least Oct. 1, 2024 to give providers time to prepare.

RFI on Health Equity. Continuing its efforts to determine how the agency can leverage its data collection and quality reporting capabilities to address disparities in health outcomes, CMS discusses a general framework that could be used across CMS quality programs to assess disparities through data reporting. CMS describes options to assess drivers of health care quality disparities within the IRF QRP specifically. One option to do this would be to employ performance disparity decomposition, which allows one to estimate the extent to which differences in measure performance between subgroups of patient populations are due to specific factors. Another way to determine disparities within the IRF QRP could be to adopt measures related to health equity. Here CMS describes the Health Equity Summary Score, a measure developed for Medicare Advantage plans that computes disparities in performance on measures across different subgroups as well as among different plans.

The AHA applauds CMS’s commitment to addressing disparities in health outcomes by considering creative approaches for data collection and manipulation. We agree that it is our responsibility as health care providers to improve outcomes for all our patients, but we cannot hope to affect real change without high-quality data and analysis. That said, the concept of an aggregated quality score proffered in this rule would not be a helpful step in achieving these goals, and we recommend CMS focus its efforts elsewhere.

Quality of care is complex, and outcomes are driven by a plethora of factors both within and outside of the providers’ control. Social risk factors, too, are deeply personal and historical facets of society, which manifest in nuanced and intricate ways that are difficult to capture accurately. Thus, it is hard to imagine feasibly calculating a single score that aggregates and averages performance on multiple measures across patients who identify with various subgroups of the population; it is even harder to imagine that such a score would provide useful information for either providers to use to pinpoint gaps and develop solutions to address them or consumers to use to inform decisions about where to get care.

At best, a summary score assessing performance in health equity would be ineffective, since a score like the Health Equity Summary Score merges performance for disparate groups (i.e., performance is calculated by “rolling up” scores for racial and ethnic subgroups along with those for beneficiaries who are eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid). By conflating performance on so many factors for many different kinds of patients, a summary score would actually blind consumers to how well a provider actually cared for a person demonstrating certain social risk factors.

At worst, a publicly displayed summary score could mislead consumers and providers by making grand, overarching assertions about performance on addressing disparities that contradict true quality of care. Poor performance for patients in certain subgroups would be averaged with high performance for others, resulting in middling scores allowing at-risk patient groups to slip through the cracks.

CMS offers multiple ideas in the RFIs for how it could use its tools to help providers address disparities in health outcomes. The most promising, stratifying performance on quality measures by race and ethnicity and dual eligibility in confidential feedback reports, is the exact opposite of the summary score. To optimize the ease-of-use of quality performance data, enhance public transparency of equity results, and build towards provider accountability for health equity, we urge CMS to focus on strategies to improve the consistency of collected data and capabilities to analyze that data rather than blurring important details with a summary score.

Thank you for the opportunity to comment on this proposed rule. Please contact me if you have questions or feel free to have a member of your team contact Rochelle Archuleta, AHA’s director of policy, at rarchuleta@aha.org, on any payment-related issues, and Caitlin Gillooley, AHA’s director of policy, at cgillooley@aha.org, regarding any quality-related questions.

Sincerely,

/s/

Stacey Hughes

Executive Vice President for Government Relations and Public Policy American Hospital Association