Addressing Each Community's Unique Needs

While all hospitals provide critical services and play a vital role in serving their communities, this report specifically examines the benefits reported to the IRS by Form 990 Schedule H provided to communities by nonprofit hospitals and systems. Nonprofit hospitals make up the majority of the U.S.’s community hospitals and account for nearly three-quarters of all community hospital admissions. They play a critical role in providing essential care and services tailored to the unique needs of their communities. Beyond offering 24/7 emergency, acute, and chronic care, they support initiatives to make communities healthier and invest in research, medical innovation, and workforce development. These benefits provide invaluable support to communities across the country, and it is critical to take a comprehensive view of their provision and impact.

To qualify for tax-exempt status under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code, nonprofit hospitals must demonstrate that they provide broad community benefits and serve the public interest. Hospitals report these benefits to the IRS through Form 990 Schedule H, which groups them into several different categories. This report focuses on eight key areas of benefits reported under Part I of Schedule H to highlight the dynamic relationship between nonprofit hospitals’ provision of benefits and the evolving needs of their communities.

- Nonprofit hospitals provide numerous community benefits in addition to financial assistance. These benefits are tailored to meet the evolving needs of their communities. Hospital resources are finite, and therefore, their allocation varies based on community needs, which are influenced by factors such as demographics and economic conditions. Additionally, regulatory changes may lead to shifts in spending across these categories over time (Figure 1). It is imperative that policymakers, researchers and the public take a holistic view of how nonprofit hospitals serve their communities.

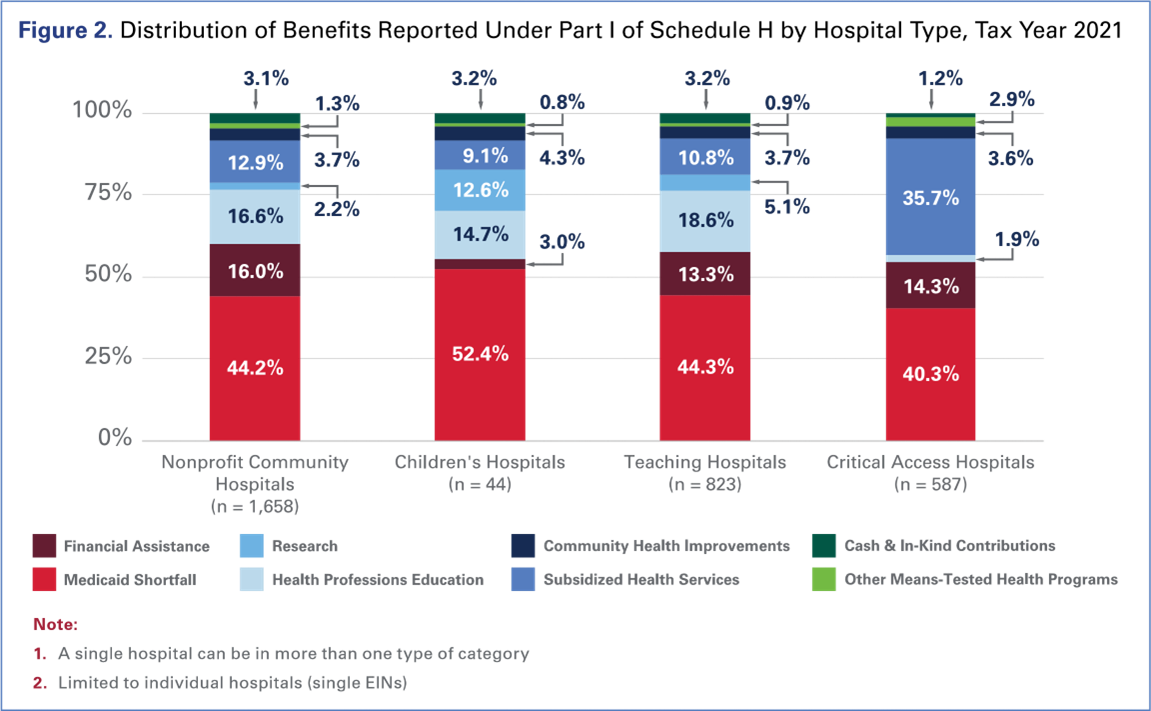

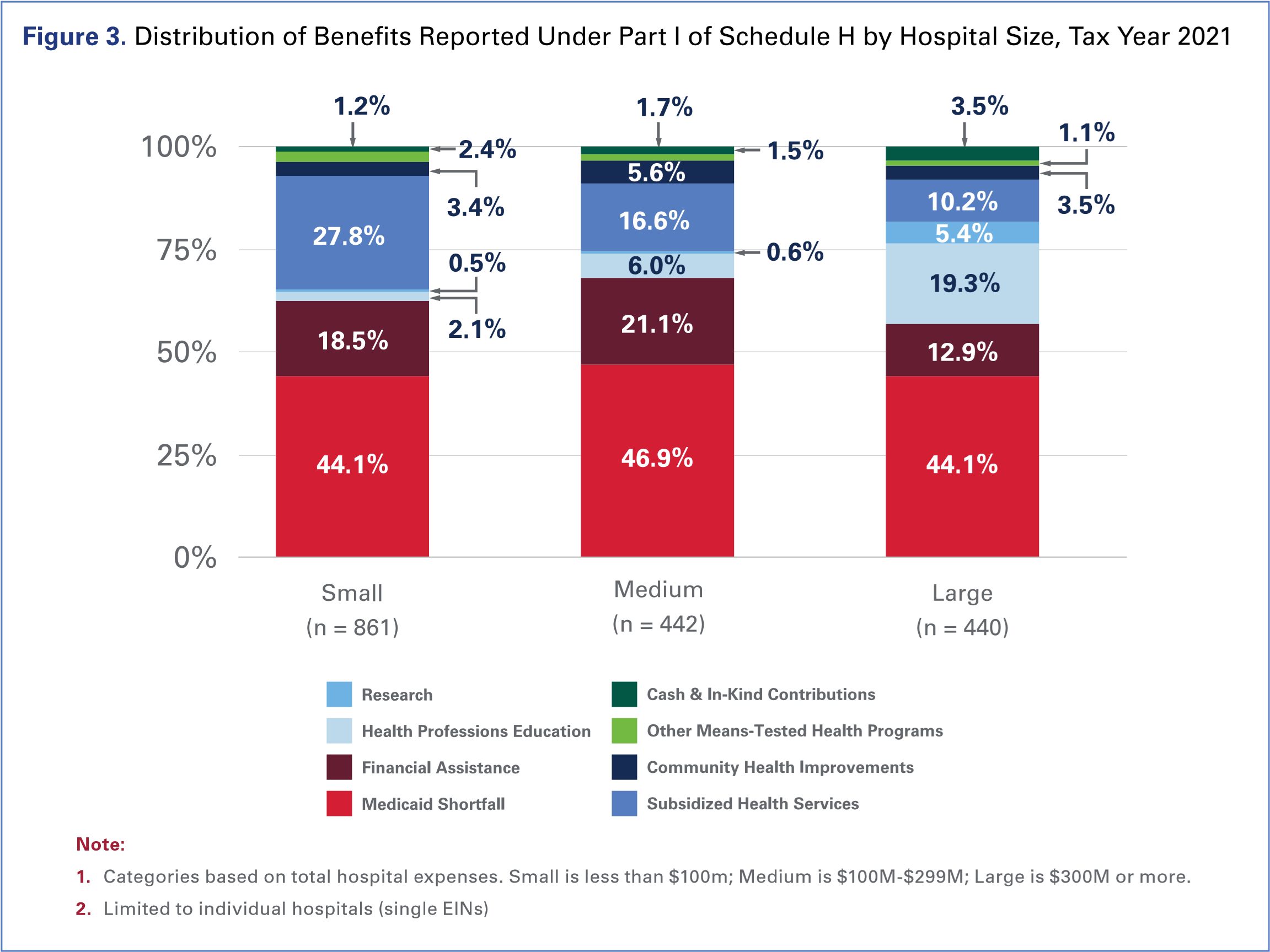

- Community benefits vary by hospital characteristics. Community benefits vary based on the type of patients the hospital serves (e.g., children), core functions (e.g., teaching or research), status as a sole provider in rural or underserved areas, and size.

Providing care at a loss to low-income patients covered through Medicaid and those in need of financial assistance are important and related components of community benefit. Shifts in federal and state policy can significantly impact the distribution of community benefits from year to year. For example, Medicaid expansion resulted in an increase in Medicaid shortfall, as more low-income individuals gained coverage under Medicaid. At the same time, the need for financial assistance for uninsured individuals declined as more individuals gained coverage. As a result, hospitals experienced an associated increase in Medicaid shortfall (given the larger number of Medicaid beneficiaries) and a decrease in financial assistance (given the smaller number of uninsured individuals). These and other policy changes, while not intended to impact hospitals’ provision of community benefits, will influence how benefits are delivered in relation to each other.

Non-governmental, nonprofit hospitals make up the majority of the U.S.’s 5,129 community hospitals and account for nearly three-quarters of all community hospital admissions.1 Nonprofit hospitals and health systems, in addition to providing critical emergent, acute, and chronic care, give back to their communities in multiple ways to meet the unique needs of the people they serve.

Nonprofit hospitals ensure access to health care for low-income individuals and families by absorbing below-cost reimbursement from means-tested government programs and providing health care to those who might otherwise struggle to access care. They promote healthier communities by helping patients navigate and find support for a variety of health and community needs. This includes providing health screenings, transportation to medical appointments, education and other community health programs like vaccination clinics, and addressing many other needs that affect their communities’ health and well-being. Additionally, many nonprofit hospitals invest in lifesaving research and medical innovation, train the future medical workforce, and subsidize vital health services, such as burn, behavioral health and neonatal units, which are essential resources provide 24/7 365 days a year for communities nationwide. Critically, these efforts are tailored to meet the evolving, specific needs of their communities, allowing hospitals to provide targeted, high-quality care and address broader health issues in a way that most directly benefits their local populations.

Recent discussions of non-profit hospitals and their tax-exempt status have focused on concerns regarding specific measures of benefits while ignoring others in a way that misrepresents the extent of the community benefits provided. Every community is different, and the benefits and services nonprofit hospitals provide are similarly unique and tailored to those community needs. It is imperative that policymakers, researchers and the public take a comprehensive view of the numerous ways nonprofit hospitals serve their communities.

To qualify as federal tax-exempt entities under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code, nonprofit hospitals and health systems must “demonstrate that they provide benefits to a class of persons that is broad enough to benefit the community and operate to serve a public rather than a private interest.” The U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS) sets out a series of factors, known as the “Community Benefit Standard,” to demonstrate community benefit.2

Nonprofit hospitals are further required by law to report on these benefits to the IRS through Form 990 Schedule H (hereinafter Schedule H). Though the Schedule H requires reporting on a broad set of activities and expenses, this analysis focuses only on the eight categories of benefits reported in Part I: Financial Assistance and Certain Other Community Benefits at Cost (Table 1). The purpose of this analysis is to show how these categories relate to each other and why they may differ from hospital to hospital or community to community.

Table 1. IRS Form 990 Schedule H Reporting Categories3

| Schedule H Section | Schedule H Category | Definition |

| Part I: Financial Assistance and Certain Other Community Benefits at Cost | Financial assistance* | Free or discounted health services provided to persons who cannot afford to pay all or portions of their medical care and who meet the organization's financial assistance policy criteria. |

| Medicaid shortfall | The difference between the cost of care provided under Medicaid and the revenue derived therefrom. | |

| Other means tested government programs | The difference between the cost of care provided under non-Medicaid means-tested government programs and the revenue derived therefrom. | |

| Community health improvement services | Activities and programs for the express purpose of improving community health. Such activities focus on health promotion, wellness, prevention, and address social needs. | |

| Health professions education | Educational programs that result in a degree, a certificate or training necessary to be licensed to practice as a health professional, as required by state law, or continuing education necessary to retain state license or certification by a board in the individual's health profession specialty. | |

| Subsidized health services | Clinical services provided despite a financial loss to the organization. | |

| Research | Any study or investigation the goal of which is to generate increased generalizable knowledge made available to the public. | |

| Cash and in-kind contributions to community groups | Contributions made by the organization to health care organizations and other community groups restricted, in writing, to one or more community benefit activities. | |

| *Also known as charity care. | ||

While hospitals exist to serve their communities, continued government underpayment results in finite resources. As such, hospitals must make decisions on how to use these finite resources to meet the evolving needs of their local communities. Those needs vary depending on factors such as geography, demographics, payer mix and economic conditions. The spending associated with different Schedule H Part I categories has shifted over time, reflecting both the changing nature of community needs and the impact of legislative and regulatory changes

For example, the significant growth in Medicaid enrollment over the last decade has meant that more of hospitals’ community benefit resources are needed to offset the losses resulting from well documented underpayments by state Medicaid programs. From 2011 to 2021, Medicaid shortfall increased as a share of Schedule H Part I benefits by 39%. This increase was fueled by a substantial rise in the number of people covered by Medicaid following both the implementation of Medicaid expansion in 40 states and in D.C. At the same time, the share of hospital financial assistance decreased by 37% from 2011 to 2021 as the uninsured population in the U.S. declined. This decrease in the number of uninsured was driven by the Medicaid expansion, as well as the other coverage initiatives. The impact of Medicaid expansion on Schedule H Part I benefits is examined further in the Policy & Regulatory Changes and Schedule H Part I Benefits section.

For example, the significant growth in Medicaid enrollment over the last decade has meant that more of hospitals’ community benefit resources are needed to offset the losses resulting from well documented underpayments by state Medicaid programs. From 2011 to 2021, Medicaid shortfall increased as a share of Schedule H Part I benefits by 39%. This increase was fueled by a substantial rise in the number of people covered by Medicaid following both the implementation of Medicaid expansion in 40 states and in D.C. At the same time, the share of hospital financial assistance decreased by 37% from 2011 to 2021 as the uninsured population in the U.S. declined. This decrease in the number of uninsured was driven by the Medicaid expansion, as well as the other coverage initiatives. The impact of Medicaid expansion on Schedule H Part I benefits is examined further in the Policy & Regulatory Changes and Schedule H Part I Benefits section.

This report highlights the dynamic relationship between the benefits nonprofit hospitals provide and their community needs, with a focus on benefits reported under Part I of the Schedule H. It is important to look at the totality of benefits that nonprofit hospitals provide to understand the unique value they provide to the communities they serve.

Hospitals, just like the communities they serve, are not monolithic. There is considerable variation in their characteristics, including the types of patients they treat, the services they offer, and their size and scope. When examining the benefits that nonprofit hospitals provide their communities, it is important to account for these differences. The examples below highlight the ways in which different communities rely on the unique benefits and services their hospitals provide, even though those benefits and services may be different from community to community.

Nonprofit hospitals come in many different forms, including children’s hospitals, academic medical centers and critical access hospitals (CAHs). As illustrated in Figure 2, nonprofit community hospitals provide a higher share of financial assistance as a percentage of community benefit spending as compared to these other specific types of nonprofit hospitals. On the other hand, while children’s hospitals provide the lowest amount of financial assistance across hospital types, they incur the highest amount of Medicaid shortfall as a percentage of community benefit. This is because children are disproportionately covered by Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), covering 38 million children nationwide, and thus are less likely to be uninsured.4 Children’s hospitals also allocate the highest levels of benefit dollars to research, reflecting the complex and unique medical needs of the population they serve.

Teaching hospitals, with their distinct role in educating and training future medical professionals, allocate the largest share of community benefit spending to health professions education. Teaching hospitals tend to be located in large metropolitan areas and often serve a disproportionately high number of Medicaid patients, providing a significant amount of care to low-income populations.5 This means that teaching hospitals cover a greater degree of the Medicaid shortfall and, consequently, see lower levels of charity care as a percentage of community benefit spending. Teaching hospitals, which often include advanced medical research centers, also allocate one of the highest shares of benefit dollars to research.

The unique position of CAHs further illustrates the importance of evaluating the full picture of community benefits and, conversely, the risk of undermining those benefits with an unduly narrow perspective. To qualify as a CAH, a hospital must be located more than 35 miles from another hospital, must have 25 or fewer acute inpatient care beds, and generally must restrict patient length of stay to no more than 96 hours.6 These facilities are widely recognized as essential for maintaining high-quality health care access across nearly 1,400 rural areas. CAHs are often the only access point for essential health care services in their communities but low population volume makes it a challenge to finance core services that must be available in a community, generating a significantly higher share of health services expenses subsidized by hospitals at a financial loss, including clinical services like burn and wound care, behavioral health, and pulmonology.7 The critical importance of CAHs’ very presence in their communities is undeniable; the benefit they provide to their communities is self-evident. Yet, they have lower shares of financial assistance and Medicaid shortfall, given the need for them to instead use their limited resources to subsidize a greater number of core services.

Benefits also vary by hospital size, as measured by hospital expenses (Figure 3). Medium-sized hospitals provide the highest share of Medicaid shortfall (46.9%) and financial assistance (21.1%) as a percentage of community benefit spend, whereas large hospitals, which include major academic medical centers, allocate the largest share of their community benefit spend on health professions education (19.3%) and research (5.4%). Conversely, small hospitals see a significantly larger shortfall from subsidized health services as a percentage of community benefit expenses (27.8%).

In addition to hospital characteristics, policy and regulatory environments can significantly impact how hospitals allocate Schedule H Part I benefits year to year. Changes to coverage policies and reporting requirements, for example, can cause sizable shifts in the distribution of benefits. As such, a singular focus on a particular benefit category — such as financial assistance — can generate a false narrative of the benefits hospitals provide their communities.

The intent of Medicaid expansion was to increase access to insurance for low-income individuals across the country. Indeed, that was the result of the program, providing Medicaid coverage to individuals who were previously uninsured. As a result, hospitals saw uncompensated care levels decrease as patients who may have previously qualified for the hospital’s financial assistance policies were now receiving coverage through Medicaid and other coverage expansions, including subsidized coverage in the Marketplaces. Unsurprisingly, hospitals then generally experienced increases in their coverage of the Medicaid shortfall and decreases in financial assistance expenses.8

This trend is evidenced by data from hospitals located in states that have expanded Medicaid. After Medicaid expansion took effect, these states saw a 34% increase in Medicaid enrollment, covering 13 million new Medicaid beneficiaries.9 As a result, hospitals in Medicaid expansion states experienced an increase in their Medicaid shortfall, with an associated decrease in financial assistance, as individuals who were previously uninsured and would have otherwise sought financial assistance were now enrolled in Medicaid. This rise in Medicaid coverage and reduction in financial assistance following Medicaid expansion was a widely expected trend among policymakers and researchers.10 As shown in Figure 4, Medicaid shortfall expenses for hospitals located in expansion states were 2.4% of total expenses in the year before those states implemented expansion. Three years after expansion, Medicaid shortfall expenses increased to 3.2%. In contrast, hospitals located in the non-expansion states had Medicaid shortfall and financial assistance levels that remained approximately the same before and after 2014.

Other policy changes have caused substantial shifts in the allocation of hospitals’ Part I benefits and further illustrate the complexity of Schedule H reporting. For example, significant shifts resulted from a 2014 regulatory change in how research expenses were accounted for and reported to the IRS. This change required hospitals to report restricted research grants and contributions that were used to provide benefit expenses as offsetting revenue, meaning that grants and contributions for research were subtracted from the total research expenses reported. This accounting shift resulted in a net reduction in the reported benefit expense for research.11 The data show that the share of research expenses (as a share of total Schedule H Part I benefits) decreased by 59% between 2013 and 2014, dropping from 11.1% to 4.6%. But in reality, the actual investment in research by nonprofit hospitals did not decrease; the decrease is attributable to this reporting change.

Nonprofit hospitals provide a broad array of benefits that vary depending on the unique needs of the communities they serve, as well as federal, state, and local laws and policies that may affect their operations. The data clearly show that it is essential to holistically examine community benefits in the context of the local community needs and policy landscape when assessing how nonprofit hospitals contribute to their communities. Nevertheless, some stakeholders have argued that the value of community benefit should be measured solely by the provision of financial assistance or some other limited combination of benefits.

Beyond what is reported on the IRS Form 990 Schedule H, nonprofit hospitals engage with their communities in a variety of meaningful ways that advance health and well-being. For example, hospitals partner with a range of local organizations to address community needs, such as housing and health screenings, as well as with local health departments in emergency preparedness and response efforts.

It is important to take a comprehensive view of community benefits and the ways nonprofit hospitals are impacting the health of their communities. Nonprofit hospitals and health systems remain steadfastly committed to addressing the unique challenges of the communities they serve and effectively allocating their finite resources to improve the health of their communities.

![]()

The community benefit expenses used for this report are those reported to the IRS net of any offsetting revenue. Net community benefit expenditures were summed across hospital employer identification numbers (EINs) and expressed as either a percentage of total Schedule H Part I benefits or a percentage of the total EIN expenses reported by the same hospitals.

To get total EIN expenses, hospital level expenses were taken from a RTI International analysis of the Community Benefit Insight (CBI), a publicly available database that aggregates U.S.-based nonprofit hospital community benefit spending data reported to the IRS, for years 2011 to 2021, and the AHA’s Annual Survey of Hospitals, for the equivalent tax year and summed up to the EIN level under which those hospitals reported.12 Numbers and Figures include all EINs unless otherwise specified.

For purposes of the IRS Form 990 Schedule H (Schedule H), the tax year is equivalent to the calendar year in which the reporting year begins (e.g., a fiscal year beginning Oct. 1, 2021, would report under tax year 2021, not under the fiscal year end of Sept. 30, 2022).

Hospitals submit a Schedule H for a single hospital (individual Schedule) or as part of a combined Schedule that includes other hospitals (group Schedule), depending on their organizational structure. The 2020 file contains 2,288 Schedules. Upon review, AHA identified 2,790 total hospitals in the Schedule H data file and matched these records with the AHA Annual Survey database.

Size

Definition: Categories based on total hospital expenses.

- “Small” is less than $100M.

- “Medium” is $100M-$299M.

- “Large” is $300M or more.

Source: AHA 2022 Annual Survey

Critical Access Hospital

Definition: A critical access hospital (CAH) is a hospital designated as a CAH by a state that has established a State Medicare Rural Hospital Flexibility Program in accordance with Medicare rules. To qualify as a CAH, a hospital must be in a rural area, located more than 35 miles from another hospital, limited to a maximum of 25 acute inpatient care beds, and maintain an annual average patient length of stay of 96 hours or less for acute care. Further details about the criteria for the CAH designation can be found at CMS.gov.

Source: The national CAH database is maintained by a consortium of the Rural Health Research Centers at the Universities of Minnesota, North Carolina-Chapel Hill, and Southern Maine, and funded by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy. The list contains the most current information and is updated regularly based on CMS reports, information provided by state Flex Coordinators, and data collected by the NC Rural Health Research Program on hospital closures.

Nonprofit Community Hospital

Definition: Nonprofit community hospitals are defined as all nonprofit, nonfederal, short-term general, and other special hospitals. Other special hospitals include obstetrics and gynecology; eye, ear, nose, and throat; long-term acute care; rehabilitation; orthopedic; and other individually described specialty services. Nonprofit community hospitals include academic medical centers or other teaching hospitals if they are nonprofit, nonfederal, short term hospitals. Excluded are hospitals not accessible by the general public, such as prison hospitals or college infirmaries.

Source: AHA Fast Facts on U.S. Hospitals, 2024

Children’s Hospital

Definition: A children’s hospital is a center for the provision of health care to children and includes independent acute care children’s hospitals, children’s hospitals within larger medical centers, and independent children’s specialty and rehabilitation hospitals.

Source: AHA 2022 Annual Survey

Teaching Hospital

Definition: A teaching hospital is a hospital that provides training to medical students, interns, residents, fellows, nurses, or other health professionals and providers, provided that such educational programs are accredited by the appropriate national accrediting body.

Source: AHA Membership Database. To be identified as a teaching hospital, the hospital site must meet at least one of the following criteria: be recognized for one or more Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education accredited programs; have a medical school affiliation reported to the American Medical Association; be a Council of Teaching Hospitals (COTH) member; have internships approved by the American Osteopathic Association (AOA); or have residencies approved by AOA.

System Affiliation

Definition: A hospital is considered “affiliated” if it is owned, leased, or managed by a health care system. Unaffiliated hospitals are called “independent” or “stand-alone.”

Source: AHA Membership Database

End Notes

- American Hospital Association (AHA), “AHA Hospital Statistics, 2023 Edition.”

- irs.gov/charities-non-profits/charitable-hospitals-general-requirements-for-tax-exemption-under-section-501c3

- irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/i990sh.pdf

- medicaid.gov/medicaid/national-medicaid-chip-program-information/medicaid-chip-enrollment-data/monthly-medicaidchip-application-eligibility-determination-and-enrollment-reports-data/index.html

- aha.org/guidesreports/2022-10-21-exploring-metropolitan-anchor-hospitals-and-communities-they-serve

- cms.gov/medicare/health-safety-standards/certification-compliance/critical-access-hospitals

- aha.org/costsofcaring

- Taitane Santos, Simone Singh, and Gary J. Young, “Medicaid Expansion and Not-For-Profit Hospitals’ Financial Status: National and State-Level Estimates Using IRS and CMS Data, 2011-2016,” Sage Journals Medical Care Research and Review 79 no. 3 (April 22, 2021): 448-457,

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), “Medicaid Enrollment Changes Following the ACA,” March 31, 2022, at macpac.gov/subtopic/medicaid-enrollment-changes-following-the-aca/. The 34% increase in Medicaid enrollment represents growth from 2013 to 2020.

- See, for example, Susan Camilleri, “The ACA Medicaid Expansion, Disproportionate Share Hospitals, and Uncompensated Care,” Health Services Research 53 no. 3 (May 8, 2017): 1562-1580, and David Dranove, Craig Garthwaite, and Christopher Ody, “Uncompensated Care Decreased At Hospitals In Medicaid Expansion States But Not At Hospitals In Nonexpansion States,” Health Affairs 35 no. 8 (August 1, 2016) 1471-1479.

- Schedule H instructions were updated in 2013 and included the following direction: “‘Direct offsetting revenue’ also includes restricted grants or contributions that the organization uses to provide a community benefit, such as a restricted grant to provide financial assistance or fund research.” While this change had the largest impact on the research category, it could also impact other benefit categories if a hospital received grant funding for activities included under another Schedule H category (e.g., a grant related to community health improvement services). See irs.gov/pub/irs-prior/i990sh--2013.pdf.

- For more information on the Community Benefit Insight (CBI), see communitybenefitinsight.org/.