AHA Comments Opposing the 340B ACCESS Act (H.R. 8574)

July 26, 2024

The Honorable Larry Bucshon, M.D.

U.S. House of Representatives

2313 Rayburn House Office Building

Washington, DC 20515

Dear Representative Bucshon:

On behalf of our nearly 5,000 member hospitals, health systems and other health care organizations, including our nearly 2,000 member hospitals that participate in the 340B Drug Pricing Program (340B program), the American Hospital Association (AHA) writes to express our opposition to H.R. 8574, the 340B Affording Care for Communities and Ensuring a Strong Safety-net (340B ACCESS) Act.

We believe this bill as drafted would dramatically diminish the program and undermine its purpose — to allow eligible providers to expand access to care for more patients and communities across the country. The 340B program is working as Congress intended. Drug companies should not be rewarded for intentionally undercutting the program and spreading misinformation about it in an effort to abrogate their 340B responsibilities. Below we detail some of our primary concerns with the bill and its negative impacts on 340B hospitals and the patients and communities they serve.

Eligibility Requirements

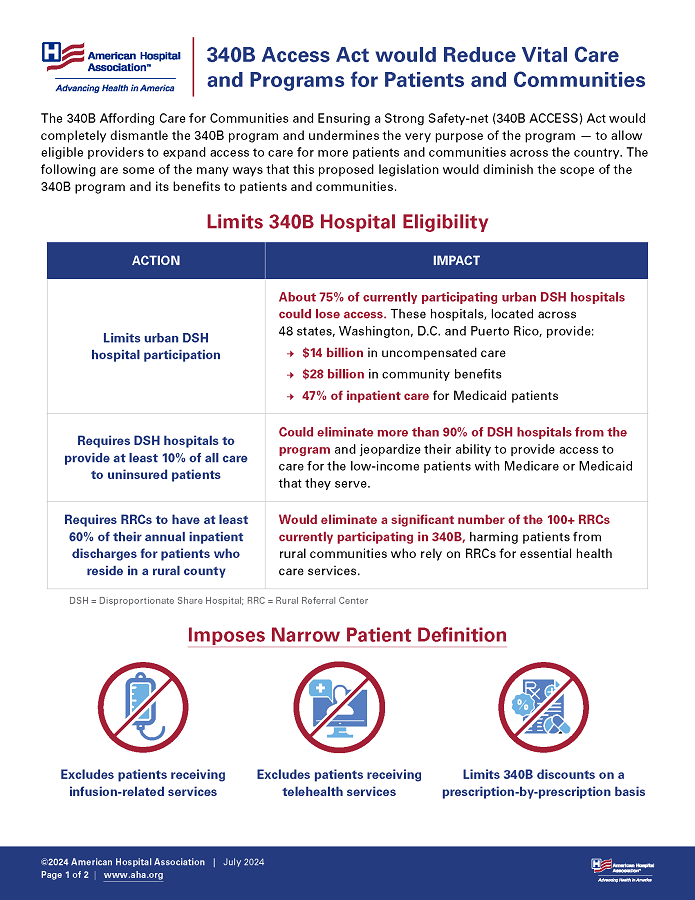

The bill would create several new eligibility requirements that would eliminate a significant number of 340B hospitals from the program. For instance, the legislation establishes a permanent moratorium on any new disproportionate share hospitals (DSH) participating in the 340B program. The bill also limits eligibility for 340B DSH hospitals located in an urban area to those that are both in the top 40% of combined Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program outpatient revenues of all acute care hospitals in their state and in the top 40% of uncompensated care costs of all acute care hospitals in their state. Not only are there methodological concerns with this criterion, but according to an AHA analysis of fiscal year 2022 cost report data, this provision alone could eliminate 75% of all urban 340B DSH hospitals from participating in the 340B program. This would undoubtedly devastate access to care for patients of these organizations and underserved urban communities across the country.

In addition, the bill changes the eligibility requirements for Rural Referral Centers (RRCs), requiring them to have at least 60% of their annual inpatient discharges be patients who reside outside of metropolitan statistical areas. RRCs provide care to rural patients and serve as a cornerstone of access to quality care in their regions. This would diminish the ability of many RRCs to qualify for the program and, like the bill’s other restrictions, harm access to care.

Finally, the bill would add as a condition of participation that hospitals and all associated child sites have charity care costs that exceed their 340B margin. This highlights a longstanding misconception of the program: that the only way 340B hospitals can demonstrate their commitment to serving low-income patients is through charity care. Exclusive focus on charity care — in direct contravention of the intent of the program — ignores the many ways that hospitals use their 340B savings to address the needs of the patients and communities they serve.1 Further, the singular focus on charity care unfairly penalizes hospitals located in states that have expanded access to Medicaid. As a result, this provision would eliminate a significant number of 340B hospitals currently participating in the program.

Patient Definition

The bill would codify an extremely narrow patient definition that would, in effect, drastically reduce the benefits of the program while creating enormous burden for providers and make it challenging for the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) to enforce. Among other problematic provisions in this section, patient eligibility would be determined on a prescription-by-prescription or order-by-order basis, rather than on a patient basis. On top of that, the bill employs restrictive timeframe requirements for when a patient must be seen to qualify for 340B treatment and requires those visits be in-person, with minimal exceptions for telehealth services or other similar care delivery mechanisms. The bill also would exclude from eligibility any infusion-only related services and would eliminate the eligibility of referral prescriptions for most 340B hospitals. Finally, some 340B hospitals also may be unable to access 340B pricing for drugs dispensed to insured patients.

Taken together, these provisions would shrink the definition of patient so narrowly that it would render the 340B program unrecognizable. As Congress originally acknowledged, it is important for the patient definition to be both flexible and durable, as health care delivery mechanisms continue to evolve.2 For example, when Congress originally enacted the 340B statute, it did not envision telehealth as a means for patient care; today, telehealth is common. Fortunately, HRSA’s 1996 patient definition guidance provides the appropriate flexibility needed to account for changes in health care delivery.3 What’s more, it has proven to be enforceable and understandable, as it is already the basis for annual audits conducted by the agency. In sum, not only is this bill’s restrictive patient definition standard unnecessary but it would contravene the congressional purpose of 340B by inhibiting the ability of eligible providers to expand access to care for their patients.4

Contract Pharmacy Arrangements

Contract pharmacy arrangements that allow 340B hospitals to partner with local and specialty pharmacies to allow patients better access to their prescribed medications would be severely constrained in this proposal. Contract pharmacies are not only an integral component of the 340B program, but they also serve as important access points for patient care. Contract pharmacies ensure that patients can better access their medications and provide follow-up care as needed. These arrangements also help patients access drugs that the hospital is unable to keep in stock and/or are in limited distribution.

While the bill would codify the use of contract pharmacies, DSHs, RRCs and cancer hospitals would only be allowed a maximum of five contract pharmacies, and the location of those pharmacies would be limited. This provision would undermine the very purpose of contract pharmacies: to ensure that patients can access the drugs in the easiest manner possible. In addition, the loss of 340B savings generated from contract pharmacy arrangements would hamper efforts by 340B hospitals to better serve their vulnerable communities, decreasing access to more affordable health care services.

Furthermore, the bill would limit the ability of states to exercise their delegated powers to regulate drug distribution, which several states have successfully used to counter drug company restrictions on the use of contract pharmacies. This provision undermines states’ rights and would quash what have been successful efforts in several states such as Arkansas and Louisiana to pass laws that put an end to drug company restrictions against contract pharmacies. These laws have been repeatedly upheld in court and are another attempt to reward drug companies for flouting the law. States would be limited to only the right to implement laws to prevent 340B Medicaid duplicate discounts.

Hospitals need maximum flexibility in contract pharmacy arrangements to respond to the varied needs and locations of their patients. They are best equipped to decide which local, specialty, mail-order and other pharmacies with which they need to establish arrangements. In some cases, hospitals are responsible for patient care across a wide catchment area that can span hundreds of miles and cross state lines. Given the potential for expansive geographic reach, hospitals may need to establish contract pharmacy relationships that appear far away from the main hospital but are in fact areas where their patients live and need access to their prescribed medications. For example, some life-saving medications are only available through specialty pharmacies located hundreds of miles away from a 340B hospital; restrictions on arrangements with these pharmacies make no sense in a world where a single specialty pharmacy is responsible for shipping medications all over the country. These real-world examples highlight why strict limits on the number and geographic location of contract pharmacies would harm patients.

Child Sites

Child sites of care are extensions of the main hospital and are clinically and financially integrated into the parent hospital. They allow hospitals to maximize access to care further into their communities, creating greater access to care. This has become increasingly important as care delivery has shifted from inpatient to outpatient. These broader system-wide trends have created an environment for increased demand for outpatient care and the critical need for child sites. Consistent with the goals of the 340B program, these outpatient facilities allow 340B hospitals to expand access to their services. The scope of services offered at child sites varies based on the needs of the community. In some cases, child sites offer a broad range of care; in other cases, they offer a single service like an infusion clinic where patients can access chemotherapy necessary for cancer treatment.

Under this proposal, access to the 340B drugs would also be severely limited for child sites. All hospital child sites would be required to be wholly owned by the hospital, which would not sufficiently account for the wide range of relationships that exist in the real world. For example, some child sites are successfully operated as joint ventures with other entities so that multiple parties can share the cost of increasing access to care, but these would not qualify under the bill. The bill would impose two additional restrictions on child sites. First, the bill would require certain child sites to have charity care levels that are greater than or equal to the charity care levels provided at the hospital’s on-site clinics or the state average. Second, child sites would need to apply the same financial assistance and sliding fee scale policies as the parent hospital and be in a health professional shortage area. Taken together, all these restrictions would severely diminish 340B hospitals’ presence in communities, which will result in less access to care.

Broader system-wide trends have hastened the need and demand for outpatient care, and the growth of child sites is simply an effort to meet that patient demand and expand access to outpatient care. The exact number of 340B child sites has often been mischaracterized and miscalculated. HRSA mandates that covered entities register every site of care, even if they are located at the same physical address. Therefore, a 10-story building where each floor is a different outpatient department may need to be registered as 10 different child sites, even though they share the same physical address and are essentially a single outpatient facility. As a result, the actual growth of child sites is far less than what drug companies and others have misleadingly asserted.

Finally, the discounts drug companies provide to 340B hospitals remains a small share of their revenues — approximately 3.1% of drug companies’ global revenues.

Transparency

340B hospitals and the AHA are committed to ensuring transparency in the program and recognize the important role it plays in promoting program integrity. However, any transparency measures should be meaningful, accurate and mitigate unnecessary burden. Among many problematic provisions in this section of the bill, the singular focus on charity care reveals the misguided belief that the provision of charity care is the only way 340B hospitals can demonstrate their commitment to the patients they serve. For example, examining just “charity care” fails to capture 340B savings used to furnish behavioral health treatment, medication management therapy or opioid treatment — services that are just as important to patients as financial assistance.

The bill also fails to account for the fact that 340B hospitals already report a variety of information to demonstrate their commitment to providing care to underserved populations. Under the tax code, 340B hospitals report uncompensated care, charity care and other benefits provided to the communities they serve through both their annual Medicare cost reports and the IRS 990 form required for tax-exempt organizations. Of note, the most recently available IRS 990 data show that 340B hospitals provided nearly $84.4 billion in community benefits in 2020 alone. Further, the increase in community benefits has outpaced the increase in 340B discounts that hospitals have received, illustrating the outsized nature of hospitals’ commitment to expanding access to care for the patients they serve. In addition to these data that are publicly available, HRSA requires separate reporting during its annual 340B hospital certification process including registration of child sites and contract pharmacies.

Finally, the AHA has established its 340B Good Stewardship Principles, which ask 340B hospitals to voluntarily commit to publicly disclosing their 340B savings, sharing how those savings are used to benefit the communities they serve. Over 1,300 340B hospitals have signed this pledge and many more hospitals continue to voluntarily share their use of 340B savings publicly, underscoring the collective commitment of 340B hospitals to transparency.

Enforcement Actions Against 340B Hospitals

Finally, the AHA takes issue with the punitive punishments that this bill, if enacted, would impose on 340B hospitals. In particular, the imposition of harsh civil monetary penalties and the immediate deregistration of covered entities after a single violation is not commensurate to the “harm” resulting from that violation. The AHA cannot think of a remedial scheme in federal law; indeed, far more significant violations in other federal programs — including serious fraud and abuse — are typically treated less harshly than this bill would treat minor transgressions of the 340B statute. It is also egregious that there is not a single provision in the bill that holds drug companies accountable for any violations of the law.

For over 30 years the 340B program has served as a lifeline for providers to maintain, improve and expand access to care. If enacted, this bill would devastate the hospitals that provide the most care for vulnerable Americans.

For the reasons outlined above, the AHA respectfully opposes the 340B ACCESS Act. If you have any questions, please contact me or Aimee Kuhlman, AHA vice president for grassroots and advocacy, at akuhlman@aha.org.

Sincerely,

/s/

Stacey Hughes

Executive Vice President

Government Relations and Public Policy

- H.R. Rep. No. 102-384(II), at 12 (1992)

- H.R. Rep. No. 102-384(II), at 12 (1992)

- https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-1996-10-24/pdf/96-27344.pdf

- H.R. Rep. No. 102-384(II), at 12 (1992)